Changing Course

A distinctive partnership between the School of Nursing and Emory Healthcare offers graduate students full-time employment after graduation—and brings the latest operational lessons into the classroom.

Daniel Martell will never forget the first time he administered a COVID-19 vaccine to a patient. It was March 2021, and he remembers the woman sitting in her chair, looking up at him, willingly letting a nursing student give his first shot.

“There’s a unique bond in a moment like that,” he says. “There’s a shared vulnerability.”

It was a meaningful moment for Martell, who until a few months earlier had earned his living as a logistics manager in the airline fuel supply industry. Unfulfilled and restless in his day job, he had started thinking about a career in nursing. Enter the InEmory program, an academic practice partnership tailor-made for students like Martell who hold bachelor’s or master’s degrees in other fields but are ready for a change of course. A fifteen-month accelerated master of nursing (MN) program for students wanting to work as RNs, InEmory guarantees its graduates two years of full-time employment at Emory Healthcare. It’s a win-win situation—for the new nurses and for the clinical units that help train them.

After taking the necessary prerequisites and applying to the InEmory program, Martell relocated from Dallas to Atlanta to begin his nursing education. Overnight, his life changed. Nursing, he says, has gotten him out from behind a desk. It has given him a chance to connect with others and to serve.

Daniel Martell

A call to action

Even as growing numbers of nurses are leaving their jobs during the COVID-19 pandemic, applications to nursing schools nationwide have surged. The American Association of Colleges and Nursing reports that enrollment in bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral nursing programs increased 5.6 percent from 2019 to 2020, with more than 250,000 new students. At the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, this trend is especially strong in the prelicensure population. “We’ve seen at least a 20 percent increase in this group over the last eighteen months in applying to nursing school,” says Katie Kennedy, senior assistant dean of admission and financial aid.

InEmory targets a particular subset of these applicants, those who already hold degrees in other fields but want to pivot into nursing. Some are young, in their twenties. Others have spent many years in diverse professions—public health, law, or graphic design, to name just a few examples.

The pandemic isn’t discouraging these individuals from applying. “When natural disasters happen, some people want to jump into action and help,” says Kennedy, who likens the present rise in nursing school enrollment to Americans joining the military after 9/11. “For these people, the pandemic is their call to action. We’re even starting to see applicants who had COVID-19 and want to give back by becoming nurses themselves.”

Accelerated programs offer accessibility and flexibility, key draws for second-career applicants. InEmory students are known as InEmory Scholars, and each receives a $10,000 scholarship over four semesters. In their final semester, students apply for jobs throughout Emory Healthcare and are shepherded through the interview and placement processes.

When the program launched, placements were limited to the medical and surgical units of the hospitals. Today, options have expanded to include specialized units such as cardiology, oncology, and labor and delivery—as well as some ambulatory units.

Once placed, graduates will spend their twelve-month nursing residencies and the year following in the new positions, and hopefully they will choose to stay on well past the two-year mark. Good nurses are in high demand just about everywhere.

“We were looking for something unique,” says Sharon Pappas, chief nurse executive at Emory Healthcare and co-creator of InEmory with School of Nursing Dean Linda McCauley. “We wanted something where health care and education could work closely together. We wanted to create a curriculum as well as a process that prepares nurses to practice at Emory Healthcare.”

Educating for culture

To excel at a place like Emory, nursing students must learn a new culture while mastering clinical skills. Nurses who work at a Magnet-designated institution hold numerous responsibilities, from forming care teams to co-leading across disease areas and units. “Nurses today work in systems and cultures,” says Pappas. “So, there’s a real benefit to a program that helps them learn how to be decision makers at a place like Emory Healthcare while they are being trained.” Amy McKee

Martell took advantage of the InEmory nurse tech role to gain added experience. Program director Bethany Robertson reports that about half of all InEmory Scholars opt to become nurse techs, working in a clinical setting while taking coursework. Martell joined the neuroscience unit at Emory University Hospital, where he feeds patients, bathes them, takes their vital signs, and assists with activities of daily living, among other responsibilities.

“For me,” he says, “being a nurse tech has helped me get comfortable in a hospital environment. It’s a lot different than working at a computer.”

Reinforcing that hands-on learning are Emory Healthcare nurses who help teach and coordinate InEmory courses. “Nurses at EHC want to participate in this teaching enterprise,” says Robertson. “And students want to develop those connections. We’re bringing the urgency and timeliness of health care operations into the classroom, making the students’ education even more relevant.”

From the courtroom to the COVID-19 unit

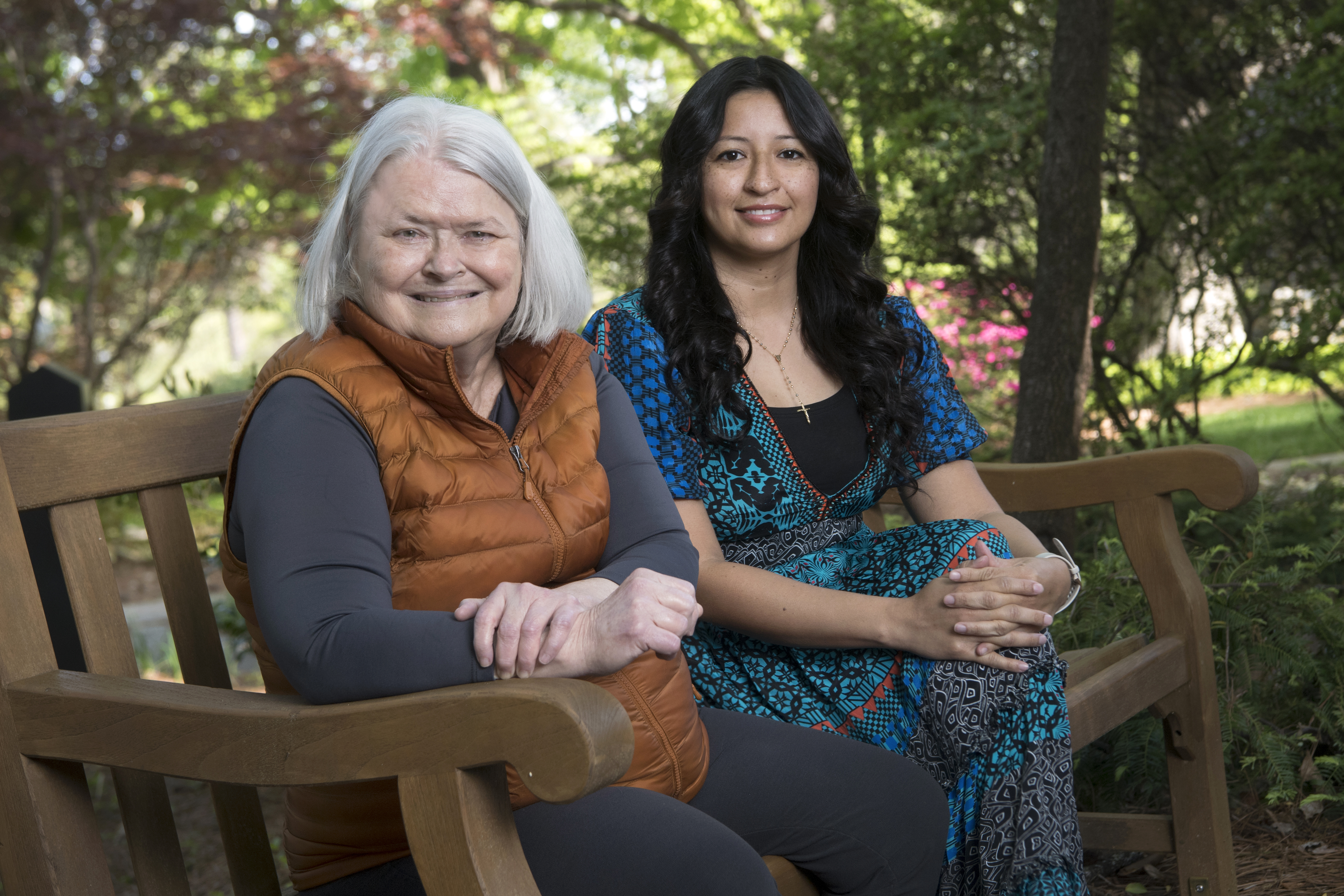

Amy McKee enrolled in InEmory’s inaugural cohort in January 2019. Today she is a nurse clinician on the complex care unit of Emory Johns Creek Hospital.

“When I walked in the door on my first day of full employment in June 2020,” she says, “this floor was the COVID unit. It was all COVID. It was intense.” Normally, a nursing resident wouldn’t be permitted to work in the COVID unit right away. But McKee had been selected back in January, right before the pandemic hit.

She was up for the challenge. Born and raised in North Dakota, McKee had spent the first part of her career as an attorney, tackling cases for the State of Minnesota. She loved being a lawyer but resigned after her first child was born. Some years later, McKee, now mother of three, wanted to reenter the work force but decided that nursing made more sense than returning to the courtroom. It also seemed a more tangible way to help others.

Shortly before her fortieth birthday, she enrolled in her first prerequisite class—chemistry, on Saturday mornings. Earning her MN at Emory over 15 months was stressful at times, she admits. The coursework was harder than law school. But she never wavered from her goal. “I love what I do,” she says of her current role, which includes precepting and training new nursing students. “I would say that pivoting in life—making a pivot in life is never a mistake. I would encourage people to just dive in.”

Transitioning to practice

Carrie McDermott, corporate director of professional nursing practice at Emory Healthcare and co-director of the InEmory program, praises the InEmory program for helping students become independent clinicians faster. “It allows us to start the transition to practice while they’re still doing prelicensure education,” she says.

McDermott helps coordinate the hiring process for graduating cohorts. She introduces InEmory students to Emory Healthcare’s talent acquisition team and to nursing unit leaders. Application submissions start in December, and students undergo interviews in January. They usually receive their offer by month’s end. They begin their jobs after May graduation.

They also get a spot at the front of the hiring line. “The HR team meets with InEmory students before they look at student applications from external schools for open positions,” McDermott says. “We aim to get our students placed before we start looking outside Emory.”

Martell, who graduates in May 2022, will be employed on the same neuroscience unit where he now serves as a nurse tech. Long term, he sees several options for his new career, from neuroscience to infectious disease to pursuing a PhD in nursing. Happily, these possibilities don’t cancel each other out. “You can move around in nursing,” says Robertson. “You aren’t limited to one track your whole life.”

For her part, McKee is firmly planted on the complex care unit at Emory John’s Creek Hospital. Even with the pressures of COVID-19, she is exactly where she wants to be. “Emory did an excellent job of academic preparedness,” she says. “And even on hard days, you know you’re having an impact. You know you’re helping people.”

Graduates like McKee are finding meaning in their careers while helping meet the growing demand for nurses. “We want to be the type of environment that allows nurses to be fulfilled personally and professionally,” says Pappas. “It’s essential for us to begin with the end in mind—to be responsive to their ideas and needs.”

In his spare time, Martel has started a peer mentoring program for InEmory Scholars. He understands that the transition from a desk job to a career at a patient’s bedside isn’t easy, especially in today’s environment. “In many ways, nurses are the front line of this pandemic,” he says. “But working during the pandemic will be an experience you can take with you for the rest of your life.”

That’s a change of course we can all get behind.