Like a Real Hospital, Like a Real Clinic

A tornado strikes a nursing home in metro Atlanta. Multiple people have been killed and severely injured. Downed power lines and ruptured gas pipes imperil the wreckage. The first emergency workers arrive on the scene, along with police, frantic family members, TV news crews — and nurses.

In this case, they are students, because this is a disaster simulation, one of many that will be staged at the new Emory Nursing Learning Center to help prepare nurses for the world of crises and complications they may face in their practice.

On the terrace level of the facility, in what had been for six decades the basement of four Decatur banks, instructors will use a warren of exam rooms and skills labs to train nurses with scenarios they will face the rest of their careers: everything from childbirth to geriatric care, not to mention traumas like those depicted in the disaster drill.

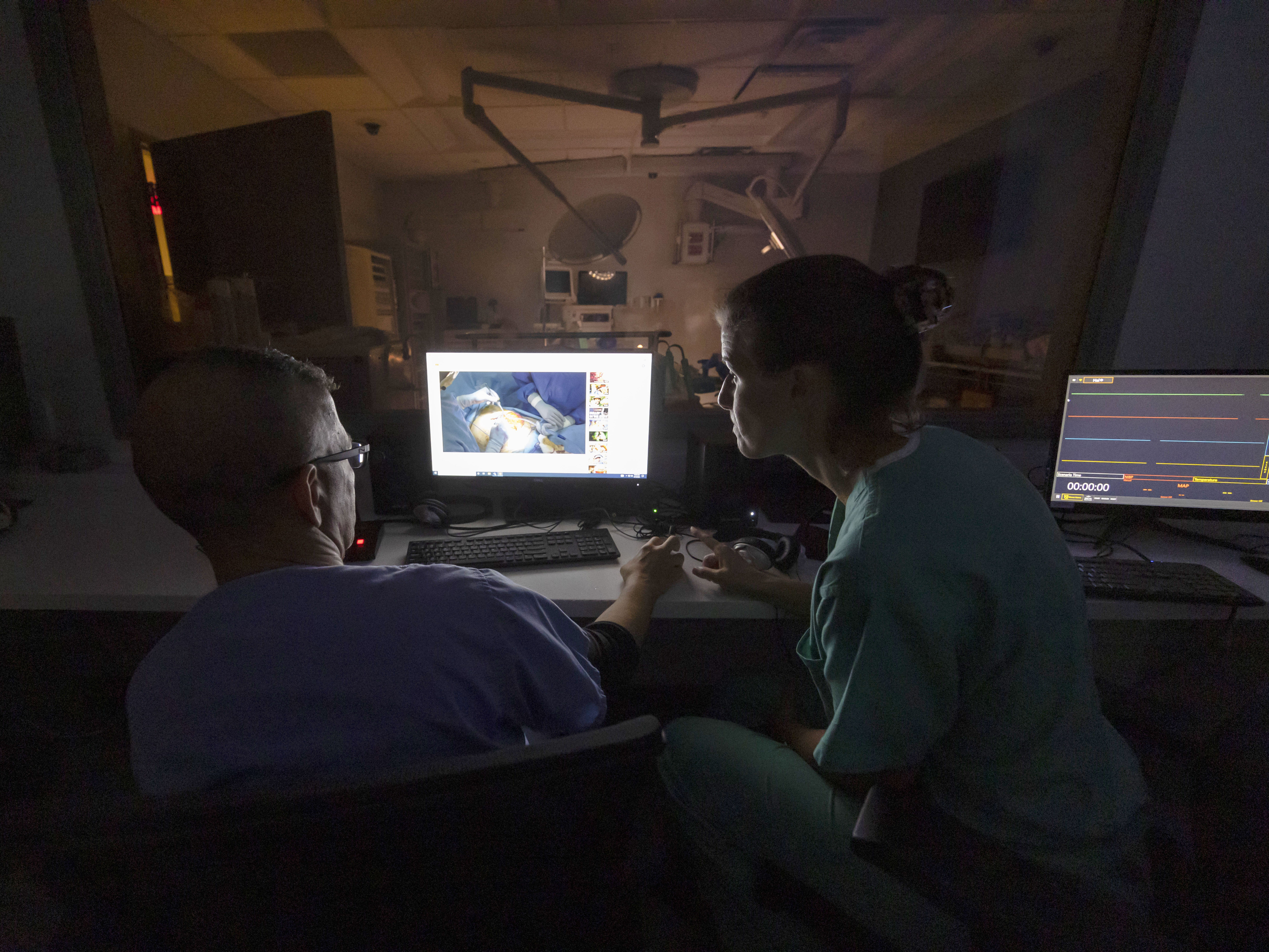

At the center of the honeycomb, the former bank vault has been remodeled into the Vault Skills Lab, a large rectangular space with eight patient beds and a control room behind mirrored glass where instructors will oversee classes and operate the high-tech manikins that nurses will practice on.

“It mimics what students will see in an actual clinical environment,” says associate dean Beth Ann Swan, PhD, RN, FAAN, executive director of the center. “The latest bed. The latest headwall. Computers on carts. The same electronic medication dispenser machines that Emory Healthcare has. What the students will see in the Vault and all the skills labs are in hospitals around the city.”

Swan started nursing school during the 1970s and marvels at how far nursing education has come since she was practicing injections by sticking oranges and occasionally her friends. But to truly appreciate the advances represented by the learning center, you must go back even further to the experience of another nurse. She’s the one whose name happens to be on the plaque outside the Vault.

THE VALUE OF HANDS-ON EXPERIENCE

When Kay Chitty, 65N, 68MSN, EdD, attended Emory’s nursing school during the 1960s, the skills lab was on the sixth floor of Emory University Hospital, and students used manually cranked beds to practice on loose-limbed dolls that were little more than crash test dummies. There was a baby doll and an adult model everyone knew as Mrs. Chase.

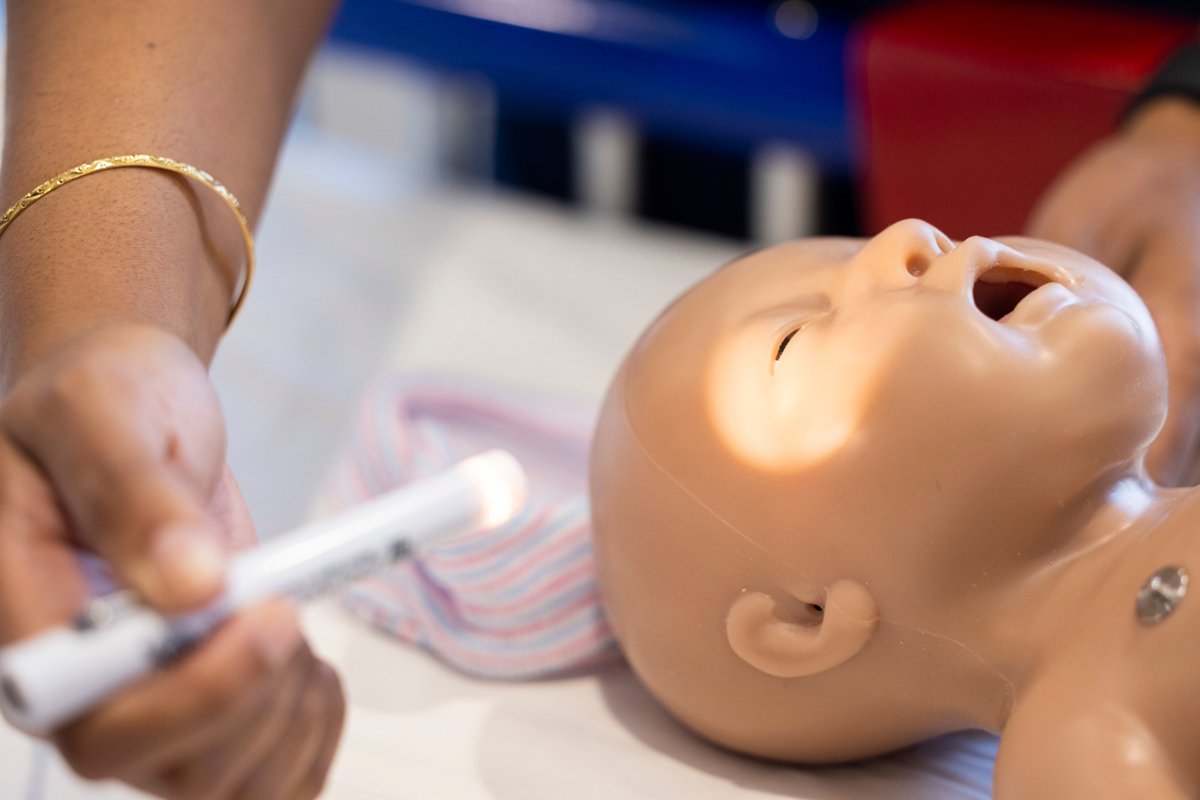

“I remember moving Mrs. Chase to one side so we could practice how to make a bed,” Chitty says. “You could put a tube down the baby’s mouth and put it in her nose, but you couldn’t do much else.”

Chitty went on to a distinguished career as a nurse practitioner and nursing school administrator in South and North Carolina and Tennessee. Now retired and living with her husband near Charleston, South Carolina, she has been supportive of her alma mater for years. When she considered philanthropic opportunities at the learning center, she thought back to her days as an Emory student.

“I got a fabulous nursing education at Emory,” she says, “and most of us passed our boards on the first try. But somewhere in my reptilian brain I could hear what people sometimes whispered about Emory nurses back then. They said we could theorize and conceptualize, but we couldn’t catheterize. They meant that we had book learning but didn’t have as much practical, hands-on experience.”

The Vault appealed to her because she didn’t want anyone to say that about an Emory nurse again. She and her husband made a naming gift. As a result, the terrace-level room designed to be the nerve center of simulations and hands-on learning for students is now called the Kay & Charles Chitty Vault Skills Lab.

The Chittys toured the facility late last year, donning hard hats and face masks to see a space that was in the process of being transformed from bank vault to state-of-the-art laboratory. They could see oxygen and suction lines in the open walls and what seemed liked miles of wiring in the unfinished ceiling.

Chitty thought about her days at Emory and the days to come in the learning center. “It’s the difference between Galileo’s telescope and the Webb telescope,” she says. “We couldn’t have imagined this when I was a student.”

MORE NEEDED SPACE

Without exception, the nursing professors who will use the new learning center say the added space is one of its greatest attributes. On the terrace level alone, there are 12 exam rooms, eight debriefing rooms, three high-fidelity simulation rooms, a high-fidelity operating room, a high-fidelity labor and delivery room, a classroom, a lounge for actors who play standardized patients, six control rooms, and four skills labs in addition to the Vault Skills Lab.

“It’s going to be so much easier staging simulations in the new center,” says associate professor Jeannie Rodriguez, PhD, RN, who directs Emory’s pediatric nurse practitioner primary care program. “Until now, we had to run primary care simulations at Wesley Woods and acute care simulations across Clifton Road at the School of Nursing. Now we can do it all at one location. I foresee that this will be the primary building where many of our students will do their work on campus.”

Having more space will also allow instructors to run more simulations in a given day. “It takes time to set up childbirth scenarios because it’s so messy,” says senior instructor Wendy Gibbons, DNP, CNM, who teaches midwifery. “We’ll have more room to debrief and discuss in a confidential manner.”

Nursing professors were consulted early and often in the design and outfitting of the skills labs. Concentrating instruction in one place will allow for scenarios that can anticipate the continuum of care that many nurses will face after graduation. Students might practice simulations on a patient who comes in for emergency care, for instance, and then follow up with the patient during outpatient encounters, telehealth conferences, or visits to a simulated residence — the home lab — created for such training on the second floor.

Tracey Bell, DNP, NNP, assistant director of the neonatal nurse practitioner program, is looking forward to using the new — and larger — space for the progressively challenging simulations that faculty devise. Students will experience a variety of scenarios involving preterm, freshly born, and older infants, some of whom will have mothers and parents portrayed by standardized patients with different skin tones and ethnicities. Scenarios will play out in delivery room and clinic settings, where students will fine tune their skills in teamwork, triage, and delegation.

“One of the problems we see with students is their inability to suspend disbelief,” Bell says. “This is going to be one of the most up-to-date simulation situations at any nursing school. It’s as close to real life as we can get it.” Faculty members observe students in the OR with the help of high-tech cameras, monitors, and manikins.

MULTIPLE MANIKINS

The learning center has 25 manikins, two-thirds of them high-fidelity models. The artificial patients allow students to practice the clinical skills they will need for the rest of their working lives.

Most of the manikins have proprietary names given by their manufacturers: preemie Hal, pediatric Hal, child-bearing Victoria, newborn Super Tory, adult Nurse Anne. The newest addition is Emory Hal, which operates via artificial intelligence and is the first of its kind in the world. Emory is the only nursing school to have this model to date. The manikins can breathe, hemorrhage, have seizures and heart murmurs, and change color to exhibit jaundice. Nurses can place catheters and chest tubes in them and even check their breasts for lumps. Two instructors typically run simulations, one focused on students and the other on operating the manikin, sometimes talking on behalf of the patient through a two-way audio system.

This summer, several Emory nursing students visited the learning center to look around. They did a dry run checking vital signs on a manikin named Susie, a middle-aged woman with mocha-colored skin — like patients, manikins come in all skin tones. With her neat, medium-length reddish hair, she looked like she could have been a bank employee — except that she wore an oxygen mask. She made breathing sounds and periodically blinked her eyes.

“Blood pressure normal,” one student said, looking at the monitor. Another took Susie’s pulse and listened to her computer-generated heartbeat.

“This is really something,” said Shannon Martensen, an MN/MSN student from San Diego, as she took in the room. “When you see that vault door, it feels like you’re robbing a bank.”

For a nursing student, the Vault holds something incredibly valuable: the opportunity to acquire experience.