A Matter of Community, Connection, and Trust

A growing partnership between Emory’s School of Nursing and Spelman College helps create a top-educated and diverse nursing workforce to serve an increasingly diverse patient population—in Atlanta and beyond.

As our world changes, it’s becoming ever more necessary to develop a health care workforce that mirrors the patient population, and Emory University's Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing has figured out a unique way to do just that: a joint degree program with Atlanta metro area neighbor Spelman College, the nation’s top HBCU (historically Black colleges and universities).

The partnership between Emory and Spelman College is a natural fit. Emory’s School of Nursing has been a longtime leader in nursing education, consistently earning top-five spots in US News and World Report rankings. Likewise, Spelman College, the nation’s oldest institution of higher education for Black women, is known for its strong STEM curriculum and has been ranked the No. 1 HBCU by US News and World Report 14 years in a row, and is one of the country’s top institutions for sending Black women to medical school.

A WIN-WIN RELATIONSHIP

The relationship between the two schools began in 2014, with the creation of a dual-degree program designed to graduate more minority nurses into the field. Students earn their bachelor of arts degree from Spelman College, then transfer their fourth year to Emory to complete a two-year curriculum and receive a bachelor of science in nursing. But administrators soon discovered many students wanted to complete all four years at Spelman, thanks to the unique opportunities and experiences an HBCU provides. So Emory created more options for Spelman students to earn their nursing degrees—and at a quick pace. Rosiland Gregory-Bass, director of Health Careers Program at Spelman College “THIS IS A TIME WHERE STUDENTS NOT ONLY HAVE THIS DEPTH OF CONTENT ACQUISITION FROM AN ACADEMIC STANDPOINT, BUT THERE’S ALSO A PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT THAT OCCURS.”

Today, most of the students complete their undergraduate degrees in full before enrolling in one of Emory’s accelerated programs such as a bachelor of science in nursing or one of the master's programs at the school, says Jasmine Hoffman, associate dean for enrollment and communications at Emory’s School of Nursing.

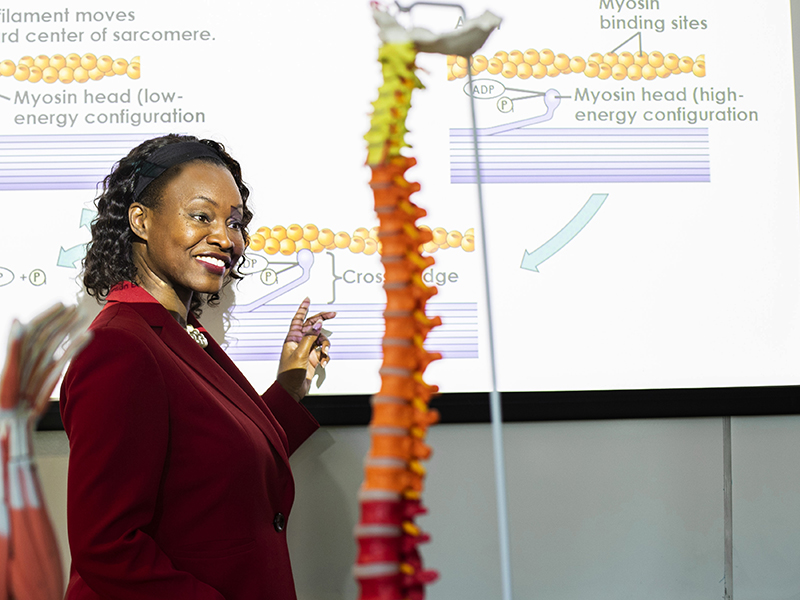

Rosiland Gregory-Bass currently serves as director of the Health Careers Program and associate professor in the Department of Environmental and Health Sciences at Spelman. She helped launch the partnership with Emory back in 2014, and, as a Spelman graduate herself, understands the importance of having that full HBCU experience.

“For many students at Spelman, this is a time where they not only have this depth of content acquisition from an academic standpoint, but there’s also a personal development that occurs,” she says. “It’s an experience that allows them to flourish devoid of any societal challenges associated with racism or other discriminatory experiences. And this is where we find individuals coming into their own.”

CONFIDENCE + NURSING EXPERTISE

That’s exactly the way recent Emory nursing graduate Jodian Grant 21N describes her time at Spelman. Grant and her family moved to the United States from Jamaica when she was 16, and as an immigrant and first-generation college student, she was unsure how she would fare in Emory’s nursing program.

“But HBCUs like Spelman really prepare Black women to go out into the world and be leaders,” Grant says. “I appreciate that now as a graduate. I see how much that experience developed me not only academically but personally. I’m more confident now. I’ve come out a different person.” Jodian Grant, recent Emory nursing graduate “PATIENTS WANT TO FEEL CONNECTED, AND THEY WANT TO FEEL LIKE THEY CAN TRUST THEIR HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS,” GRANT SAYS. “DIVERSITY HELPS YOU BE MORE RELATABLE. BECAUSE I’M AN IMMIGRANT, I CAN RELATE TO FELLOW IMMIGRANTS AND THEREFORE THOSE PATIENTS MIGHT BE MORE WILLING TO PARTICIPATE IN THEIR PLAN OF CARE.”

Grant says she decided to continue her education at Emory because she knew the program would provide the clinical time and simulation labs she needed to enter the workforce as competent as possible. Emory’s reputation as a top nursing school is well-known among Spelman graduates, and, as Bass points out, if a student is already having a great experience in Atlanta, the relationship between the two schools offers a seamless transition to continue that by enrolling in a nursing program just across town.

That was the case for Kiara Hill, whose extra high school credits led her to graduate a year early from Spelman. While she was attracted to Emory’s high-ranking nursing program, Hill also wanted to stick around Atlanta to be close to friends who were still attending Spelman. After completing Emory’s accelerated bachelor of nursing degree, she now lives in Los Angeles, where she works as a psychiatric nurse. Hill often helps with her hospital’s admissions, and feels the nursing skills she learned at Emory, such as assessing patients, has led to her success. So has the program’s emphasis on critical thinking.

“This is my first nursing job, but I know the right questions to ask to get more information,” Hill says. “I don’t have to call in my supervisor constantly because I can think through a situation and figure it out.”

SERVING ATLANTA AND BEYOND

Of the 12 Spelman graduates who have come through Emory’s School of Nursing since 2014, all have passed their NCLEX exams and are now either in graduate school or working full time—and the majority have stayed in the Atlanta area.

Jordan Murphy 15N 18G 20PhD is one such alumna. A native of Durham, N.C., Murphy graduated from Spelman with a degree in biology. She chose to continue her education at Emory because of its reputation as one of the top institutions for preparing nurses and nurse scientists and went on to earn her bachelor’s, master’s, and PhD from the school. Today, Murphy works as a pediatric nurse practitioner and director of operations at Atlanta’s Community Advanced Practice Nurses Clinic, a free health care clinic that serves homeless or uninsured families.

“BECAUSE WE HAVE SATELLITE LOCATIONS, I’M ALWAYS INTERACTING WITH DIFFERENT GROUPS OF PEOPLE. I FEEL SO CONNECTED TO THE COMMUNITY. I’VE SPENT THE LAST 13 YEARS WORKING AND VOLUNTEERING THROUGHOUT ATLANTA, AND I’M COMMITTED TO CONTINUING WHAT I’VE BEGUN HERE.”

“I love the population I work with, and because we have satellite locations, I’m always interacting with different groups of people,” Murphy says. “I feel so connected to the community. I’ve spent the last 13 years working and volunteering throughout Atlanta, and I’m committed to continuing what I’ve begun here.”

Other Spelman-Emory graduates have found positions with Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Piedmont Healthcare and the Atlanta VA Medical Center.

“Many of these students are not from Atlanta, but they fall in love with the city and decide this is where they want to help support the health care workforce,” Hoffman says. “That’s really powerful.”

It’s powerful because the Atlanta metro area has some major health and health care disparities to overcome. The city has the widest gap in breast cancer mortality rates between African American women and white women of any United States city, as well as the nation’s highest death rate for Black men with prostate cancer. A 2015 study conducted by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University found a 12-year difference in average lifespan in the neighborhoods of Fulton County, with predominantly Black areas faring worse. These neighborhoods often lack access to critical resources such as quality medical care, and because housing and food are top priorities for low-income families, there’s little to no money to spend on preventive care.

ADDRESSING DIVERSITY AND DISPARITIES

Of course, the rest of the nation isn’t immune to these disparities, which don’t exist solely within the context of race and ethnicity. Sexual orientation or identity, religion, citizenship status, and disability also contribute to a person’s ability to achieve good health. Creating a more diverse nursing workforce that is ready to address the cultural needs of patient populations can help eliminate some of those disparities. Research has shown that when nurses understand and relate to the culture and history of a patient’s community, they are able to provide more customized treatment, and patients feel more comfortable and confident in the care they are receiving.

“Patients want to feel connected, and they want to feel like they can trust their health care providers,” Grant says. “Diversity helps you be more relatable. Because I’m an immigrant, I can relate to fellow immigrants and therefore those patients might be more willing to participate in their plan of care.”

That trust can have a major impact on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of various diseases and conditions in our society, especially those that disproportionately affect African-American populations, such as heart disease and diabetes.

“I have great uncles and grandparents who don’t want to go to the doctor’s office, and I think that’s the case for a lot of Black people,” Hill says. “No one looks like them there, and therefore they can’t trust anyone. I think the more Black people we can get in the health care workforce, the more it alleviates that problem. People would be more inclined to get help and those disease rates wouldn’t be as high.”

But creating a diverse nursing workforce begins with the institutions providing nursing education and how much they strive to reflect the culture they want to see out in the world. Emory University has an Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI), and last summer the School of Nursing created its own DEI office in an effort to create a strong culture that embraces and promotes those values.

According to the office’s assistant dean, Lisa Muirhead, one of the focuses of the new office is to provide awareness and education about DEI topics, and the office’s website provides access to a variety of articles, podcasts, books, and professional development courses for the School of Nursing community.

Another focus is to enhance the nursing school’s curriculum by weaving concepts of diversity, cultural sensitivity, and social action throughout each program of study. A third goal is to create benchmarks for the recruitment of faculty, students, and staff from underrepresented communities.

“There’s a richness that diversity brings,” Muirhead says. “In order to improve the quality of our education here at Emory, it’s essential to bring together people with diverse backgrounds, life experiences, and perspectives. I believe the School of Nursing can be a catalyst for innovation and advancing education through diversity.”

The School of Nursing’s partnership with Spelman College certainly plays a role in that. But Hoffman says it’s only the beginning. Emory is working to establish a similar joint-degree program with Morehouse College, a men’s HBCU also based in the Atlanta metro area.

“We plan to continue to promote initiatives that are aimed at creating diversity in the health care workforce,” Hoffman says. “That is a real priority for the School of Nursing and for Emory as a whole.”

Photography Disclaimer: COVID-19 protocols appropriate to each setting and time were followed in taking the photographs that appear in this magazine.

At a Glance: The Spelman-Emory Dual Degree Partnership

Creates a path for graduates of Spelman College—the nation’s oldest HBCU dedicated to serving Black women—to earn a nursing degree from Emory.

Known for its strong STEM curriculum, Spelman has been ranked the No. 1 HBCU by US News and World Report for 14 years in a row and is one of the country’s top institutions for sending Black women into advanced health care and medical programs.

The nursing dual-degree program between Spelman and Emory began in 2014.

How it works: Students first complete a bachelor’s of arts degree at Spelman and then transfer in their fourth year to complete their bachelor’s of nursing degree in two years from Emory

100 percent of Spelman graduates who have completed their degree in nursing from Emory have passed their NCLEX exams and are now either in graduate school or working full time.

Most graduates of the Spelman-Emory dual-degree program have stayed in the Atlanta area.