Owning the Research

By Leslie Church

Dar es-Salaam’s Muhimbili National Hospital, with 1,500 beds, is the largest public hospital in Tanzania. To most people, that sounds like a lot of patients. But to a scientist, that sounds like a lot of data. The problem was, researchers would come from other institutions—often other countries—gather data, and then write a publication without much collaboration with hospital staff. “The hospital was incurring risk without the benefits,” says Sydney Spangler PhD MSN CNM, assistant clinical professor at the School of Nursing. “There is a lot of potential for exploitation around data,” she adds.

That’s why becoming a renowned center for research—its own research—was one of the strategic goals Muhimbili Hospital set for itself in 2017, along with improving quality of both clinical services and business operations.

Spangler is part of a three-person team of Emory faculty, along with Jason Hockenberry PhD, associate professor at Rollins School of Public Health, and Brittany Murray MD, assistant professor at the School of Medicine, who joined forces with the hospital to support its mission. The Emory-Muhimbili Partnership for Health Administration Strengthening and Integration of Services (EMPHASIS) is a five-year initiative supported by Abbott Fund Tanzania. Spangler has been helping the hospital take significant steps forward in the way it conducts research.

Sydney Spangler

Sydney Spangler

Connecting with resources in Atlanta

Muhimbili’s new research department is partially modeled on Emory’s. During a month-long trip to Atlanta, staff met with their counterparts from the Office of Nursing Research to discuss grant applications, money allocation, and bioethical standards. It’s not the headline-grabbing part of research, but funding

is the bottom line that drives the whole operation.

“This is about sustainability,” Spangler says. “Research brings money. Eventually, Muhimbili Hospital won’t have to rely on outside institutions if they don’t want to. They’ll get their own funding and do their own research.”

“Research goes hand-in-hand with clinical practice and guides the development of local treatment guidelines,” says Faraja Chiwanga, MD, head of the Teaching, Research, and Consultancy Unit at Muhimbili Hospital. “Having hospital staff as co-investigators ensures that they’re actively involved in research and hence increases their research capacity.”

To that end, a new rule was established: no outside researchers may conduct a study at Muhimbili unless a hospital staff member is a co-investigator. What impact will this have on Muhimbili’s goal to become a renowned center for research in Africa and the world?

About 200 research projects are conducted at MNH every year. Having MNH staff as co-investigators ensures that the team is actively involved in research and hence increasing their research capacity.

After securing grants, steps two and three for building research capacity go hand-in-hand: establishing a means to collect continuous, accurate data; and having the expertise to know what to do with it.

High-tech fix means better data

One of the initiative's most tangible changes came in the form of an iPad. Previously, when a baby was born in Muhimbili Hospital, nurses would lug down a series of nine enormous binders from a shelf and document different bits of information from the birth in each one. The baby’s birth weight, mother’s parity, and gravidity, C-section rates, and so on, were all reported to the Ministry of Health. The logbooks were cumbersome, and often plagued by missing data and unreadable handwriting. But inefficiency wasn’t the only problem.

“Here sat this enormous amount of data that could be used to improve clinical outcomes, but it was stuck in an outdated form of record-keeping,” says Spangler.

The iPads were a logical fix: the hospital’s occasionally unreliable internet was no problem since a SIM card could be used to maintain access to the cloud. Birth indicators and demographic information were organized under REDCap, a research database that Emory uses, offered for free in developing countries.

Already, patterns have begun to emerge from the data. It appeared that staff was underestimating blood loss from C-sections, for example. “So now they can say, if this is happening, are we under-treating blood loss?” Spangler explains.

The REDCap model has spread to other areas of the hospital: newborn units, renal services, critical care. Even the hospital administrators have adopted it, surveying employees on job satisfaction and patients on their hospital stays.

Nurse midwives enter data on their iPads.

Nurse midwives enter data on their iPads.

Nurses ask the best questions

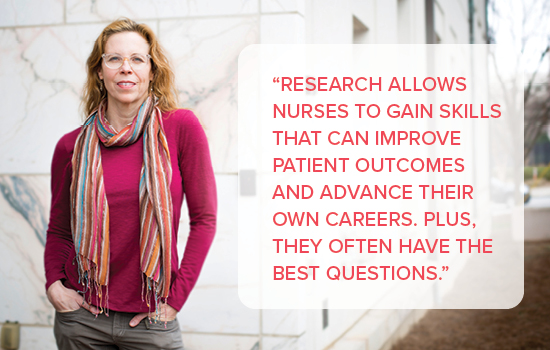

The final step in the EMPHASIS research initiative is a mentorship program where up to five Muhimbili employees will be paired with Emory faculty. The goal is for the Tanzanian investigators to conduct a two-year study and submit manuscripts for publication where they are the first author. Spangler is encouraging nurses and midwives to apply.

“Sometimes nurses get left out of these efforts,” Spangler explains. “Research allows nurses to gain skills that can improve patient outcomes and advance their own careers. Plus, they often have the best questions.”

While a PhD is usually a precursor to being a primary investigator on grants in the U.S., in other parts of the world like Tanzania, experience is more important than credentials. “They certainly don’t need a PhD to get funding,” Spangler says. “In developing countries, people aren’t always forced to go through the same systems we have here that might not work for them.”

After the mentorship program, the Muhimbili scientists will have the capacity to serve as co-investigators with academics from around the world, or with others at home in Tanzania.

“It is not the explicit goal of this research program to have a grand global impact,” Spangler says. “It’s really to benefit the local community—the staff at Muhimbili Hospital and the Tanzanians that they serve. The more people we have conducting their own research in their own communities all over the world, the better it is for everyone.”