Haiti Hope

By Pam Auchmutey

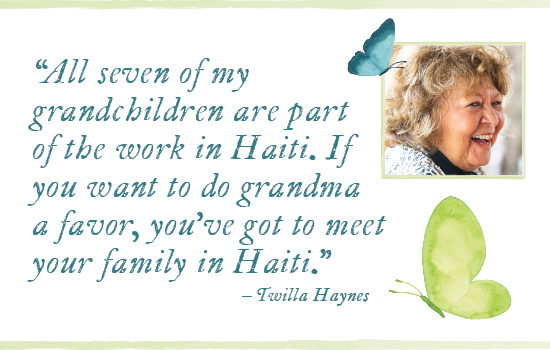

For Twilla Haynes, seated here, her work in Haiti long ago became a family affair. All seven grandchildren, along with her son Rodney Haynes, his wife Elaina, and daughters Angela Haynes-Ferere and Hope Bussenius, travel to Haiti regularly to visit Hope Haven orphanage and provide health care at several mobile sites. Photo by Kay Hinton

Editor’s note: This story was written and submitted in the days before the coronavirus pandemic began.

As the magazine goes to print, Doctors Without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières) reports Haiti’s COVID-19 figures have spiked to more than 3,000 cases and 50 deaths. The nonprofit group says that due to a lack of testing, the count is likely much higher. Angela Haynes-Ferere reports that the Hope Haven children are all sheltering in place, with food being delivered to them. She adds “unfortunately, much of the community is being impacted and we continue to seek ways to lend support. Our March and June trips were impacted, but we are looking forward to returning.”

Additionally, this story focuses on the extraordinary humanitarian efforts of nursing alumna and Emory Medal winner Twilla Haynes 80MN JD. We regret to announce that Twilla passed away on August 25, 2020, at the age of 76. Read more about the impact of her life’s work here.

The island looked picture perfect from the air—a lush, green oasis surrounded by a turquoise sea. But as the plane descended over Cap-Haitien, a port city on the north coast of Haiti, the ravages of lingering poverty and political strife were clear to see.

Allie Ankeny 19N JD MPH was aboard the plane that carried 11 Emory nursing students to Cap-Haitien for a two-week clinical practicum in population health last summer.

“I’ll never forget that moment,” says Ankeny, today one of the first graduates of Emory’s distance-based Accelerated BSN (DABSN) program. “When we landed, the contrast to our privileged lives could not have been more stark.”

A few days later, the DABSN students saw their first patients at a clinic set up outside an orphanage founded by their faculty leader, Twilla Haynes 80MN JD. “People walked for miles to get there and waited for hours to get care,” Ankeny says. “They had so many problems, and we could only treat the worst ones.”

At one point, Haynes asked Ankeny what she thought about Haiti so far. “There’s so much beauty and so much deprivation,” Ankeny told her. “I wasn’t prepared for how people live in such conditions.”

“Yes,” Haynes told her. “Haiti is a land of contrasts.”

Haynes had a similar reaction when she first traveled to the country in the 1980s. At the time, she worked for the Georgia Department of Public Health, overseeing three clinics she helped establish to serve carpet and other industry workers in North Georgia. Later, she established a clinic for underserved patients in a town near her home in rural Jackson County. She also worked with the homeless population in Atlanta and taught nursing students from across Georgia.

Haynes was drawn to serving and teaching others in North Carolina, where she grew up in the Lumbee Tribe. “I never felt that I was discriminated against,” she says. “But some of my Indian friends were not allowed to go to a county school. Knowing people who endured that made me more sensitive to the needs of families and communities.”

In 1984, Haynes accompanied Georgia nursing students on a service-learning trip to Haiti. The group helped local physicians and nurses treat hundreds of Haitians. For Haynes, the challenges—namely too few supplies and medications to treat people with typhoid fever, malaria, HIV, meningitis, and other illnesses—underscored a powerful need.

“I learned how simple it was to save lives,” she said, shortly after receiving the Emory Medal, the university’s highest alumni honor, in 2010. “We’re not talking about rocket science. It’s primary care, it’s learning about these diseases, working side by side with these strong practitioners.”

Since her first Haiti trip, Haynes has taught more than 1,500 nursing students from Emory and other Georgia schools, aided by her daughters, Angela Haynes-Ferere 91MPH 08N 09MN DNP and Hope Bussenius 93MN DNP FPN-BC, both members of Emory’s nursing faculty. In 1993, they founded Eternal Hope in Haiti (EHIH), a nonprofit that provides basic health care and nutritional services to adults and children in and around Cap-Haitien.

Through EHIH, the Haynes family (wives, husbands, children, and grandchildren) and a host of repeat volunteers (including Emory nursing alumna Cheron Hardy 03MN, a nurse practitioner in Washington, D.C.) serve approximately 6,000 patients a year. EHIH is self-sustaining, which Haynes attributes to divine intervention. Donations come in by word of mouth—from churches, businesses, friends, current and former nursing students, and volunteers who work for free and pay their own travel expenses to Haiti.

During a trip to Haiti in 1996, Haynes hurriedly wrote a personal check to lease a building to house two medically fragile babies under her care. In just 24 hours, Haynes had established Hope Haven, a home for orphaned and sick infants and children, as part of EHIH.

“I didn’t know it, but when I returned home, someone had sent me a check for $200 more than the lease for the building,” Haynes says. “That’s how our work has been made possible.”

Hope Haven currently occupies two buildings, one for boys, the other for girls. The boys live in a building that housed a clinic run by EHIH until an earthquake devastated much of Haiti in 2010. The clinic was closed to free up space for children orphaned by the earthquake.

Every three months, Haynes returns to Haiti to visit Hope Haven and oversees the health care that EHIH provides at five mobile sites in and around Cap-Haitien. The clinics operate only when Haynes is there. The most remote site is a three-hour truck ride away.

“We see the same people we’ve been taking care of for 20 years,” says Haynes. “We decided early on that if we’re going to make an impact, we’ve got to stay with the same communities to see if we can measure outcomes.”

Measures have shown improvements in controlling conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and HIV in adults and malnutrition in children.

Family matters

On previous trips to Haiti, Bussenius and her Emory graduate nursing students have provided pediatric care. A few years ago, Haiti provided a testing ground for PediaBP, an app that she developed to help nurses assess hypertension in children more quickly and easily.

Bussenius was 14 when she first visited Haiti. Her son, a high school sophomore, and her daughter, who will begin her BSN studies at Emory this fall, have volunteered with the family most of their lives.

“All seven of my grandchildren are part of the work in Haiti,” says Haynes. “If you want to do grandma a favor, you’ve got to meet your family in Haiti.”

At the moment, the Haynes family includes 66 children and young adults at Hope Haven. The youngest is 6 months old; the oldest is 24. Because Hope Haven residents do not age out of the orphanage, support for each one continues when they become old enough to enter college or learn a trade. Thirteen students are now in college. Three have finished college, the first of whom graduated from nursing school.

“Hope Haven is a little different from other orphanages,” says Haynes-Ferere, who has a grown son from Haiti. “We don’t adopt our kids out, and we don’t have a date when they need to leave. They age out as appropriate for them. They come back and have dinner together and go to church together. There’s still that sense of family.”

When Haynes founded Hope Haven, she didn’t envision helping her children transition to adulthood. Her priority was to keep sick babies and children alive and healthy. But she and the rest of the Haynes family now have a plan.

“The education piece is just as important or more so,” says Haynes, whom many Haitians call “Big Mom” in English and Creole. “The children who are in college are really doing well. Now that the oldest child has graduated from nursing school and showed the others what is possible, the children have a different spirit now. They know if they do their part, we’re going to do ours.”

Hope Haven is growing up as well. Later this year, all of the children will live together in a new building, set on six acres donated to EHIH more than a decade ago.

“It’s a beautiful piece of land,” says Twilla. “It has every fruit tree that grows in Haiti. The engineer in charge of the building project says we can put 100 kids in the building. I told him, ‘Listen, we have enough!’ That’s the potential.”

Three of the girls from Hope Haven.

Three of the girls from Hope Haven.

Nursing in a new light

During her practicum in Haiti last summer, Allie Ankeny was determined to do her best. Her first day of clinic, held outside one of the orphanage buildings, was noisy, chaotic, and unbearably hot. At 5’8, she found it difficult to stoop over young pediatric patients while fumbling with an otoscope to look into their ears. She thought about lifting her patients up on a table until learning that it was reserved for use as a pharmacy. After taking another look at the long line of patients who had waited for hours, she knelt down to meet her patients at eye level.

“Suddenly it dawned on me that kneeling in the dirt was the least I could do,” says Ankeny, who is now COO and executive director of a large pediatric practice in northern Virginia. “If I could do one thing to make a difference, that’s what I was there to do.”

Ankeny tried not to feel overwhelmed by the experience. “I want to do so much and help everyone,” she told Haynes.

Her preceptor offered reassurance. “Allie, that kid you just helped, you made their life better,” Haynes told her. “Remember, what you are doing matters to the person you are helping right now.”