Reducing hospital-acquired infections

“We owe it to our patients to create workflows and practices that protect them,” says Sharon Vanairsdale.

In the summer of 2014, Ebola virus disease (EVD) raged in West Africa with no end in sight. Working with Ebola patients in Liberia through a medical missionary program, Dr. Kent Brantly was in the heart of the storm. Brantly contracted Ebola during this time and was transferred to Emory University Hospital to be treated.

By treating the first patient with EVD in the United States, Emory and its Serious Communicable Diseases Unit (SCDU) made history and sparked national media attention. After Brantly, Emory would accept three more patients with EVD. The four Emory patients all recovered, but the fight with serious communicable diseases is far from over.

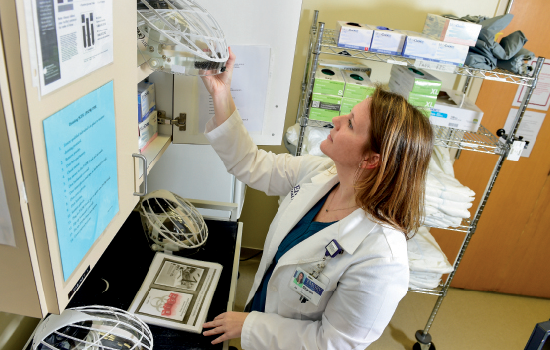

Sharon Vanairsdale 18DNP APRN is program director and lead nurse of the SCDU at Emory University Hospital and adjunct professor at the School of Nursing. Vanairsdale wants to take what clinicians have learned from treating four Ebola patients and translate it into everyday patient care.

“According to Becker’s Hospital Review, hospital–acquired infections kill 99,000 people in the United States per year,” says Vanairsdale. “What if things we did in everyday patient care could prevent this?”

Vanairsdale’s approach is to be proactive instead of reactive. Clinicians in the SCDU did not realize that four Ebola patients would be in the unit until a few days before they arrived. But the team was able to treat the patients successfully because of the proactive work they had been doing for the past 12 years.

Situational awareness and proactivity can be looked at as a three-pronged approach, says Vanairsdale, considering design, behavior, and training.

She uses the example of personal protective equipment (PPE) as an illustration of design. “Who decided to purchase these specific gowns we used for the hospital? Was it the person trying to save the hospital money, or the person who was concerned with the quality and safety of the gown?”

Health care workers’ behavior is vital in reducing hospital-acquired infections. “They should be following the same evidence-based safety protocols every time,” says Vanairsdale. “We owe it to our patients to create workflows and practices that protect them, health care workers, and the community.”

The last prong to Vanairsdale’s approach is training. She is director of education at the National Ebola Training and Education Center, or NETEC, where she trains health care workers on serious communicable diseases and correct protocol for patient care. Vanairsdale has trained more than 1,000 health care workers all over the country, conducting in-person and video conferences for professionals to learn.—Catherine Morrow