More Than a Cure

By Maria M. Lameiras | Illustration by Anna & Elena Balbusso

Advances in science and technology are enabling cancer patients to live longer than ever before. Still, the everyday reality of cancer treatment is harsh.

The concomitant effects of chemotherapy and radiation can ravage healthy tissues while battling tumors. Oral therapies can come with a startling array of potential side effects and daunting price tags.

While many researchers race to identify new targets for treatment and formulate new therapies, a growing cadre of School of Nursing researchers is leading the nation in studies that examine the patient experience and how patient-reported outcomes can inform cancer care.

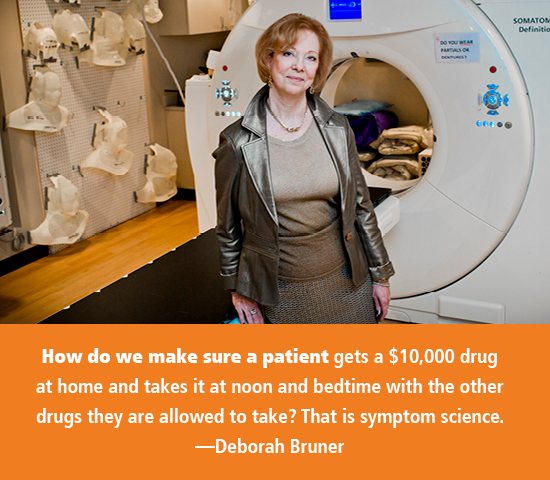

Deborah Bruner PhD RN FAAN, Robert W. Woodruff Professor of Nursing, is a well-known expert in cancer clinical trials and oncology nursing research through Emory's Winship Cancer Institute. She is associate director for mentorship, training, and education at Winship, newly designated by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) as a comprehensive cancer center for reducing cancer burden in Georgia. She is the first and only nurse to lead one of four adult NCI Community Oncology Research Programs. She also helped set new priorities for NCI clinical trials on symptom management and patient quality of life. In 2016, she was elected a member of the National Academy of Medicine.

"When you are in clinical practice, the physician mostly is interested in doing diagnostics and cure. In inpatient care, the nurse manages everything else—the symptoms related to disease and treatments, the environment around the patient to provide comfort and care, and the environment around the family to engender support," Bruner says. Nurses understand how evidence-based, supportive oncology care to families and patients decreases pain and suffering and improves quality of life. That knowledge has inspired Bruner to improve the patient experience in a rigorous, scientific way.

Over the years, her work has informed the NCI's adverse event reporting system, an important tool used to grade symptom toxicities associated with chemotherapy drugs, immunotherapies, precision medicine, radiation medicine, and surgery in cancer treatment—work that has made patient-reported outcomes as important in changing clinical practice as clinical outcomes.

Late last year, Congress passed the 21st Century Cures Act, authorizing $1.8 billion over seven years for NCI's Cancer Moonshot, a program designed to accelerate cancer research by making more therapies available to more patients, while also improving early detection and prevention of cancer.

Earlier this year, Bruner presented "Challenges in Cancer: Moonshots, Miracles, and Myths" during an academic symposium celebrating the inauguration of Emory's new president, Claire E. Sterk. In her talk, Bruner challenged the current funding model that prioritizes cures and precision treatments that benefit a fraction of cancer patients over research that benefits larger patient populations.

Because new precision medicines, immunotherapy treatments, and other "miracle" drugs are so costly, these drugs often are out of reach for the small number of patients who qualify for them. The discovery of the EGFR mutation in lung cancer offers a compelling example.

"Now we have immunotherapy drugs to treat patients with that mutation, and 10 percent of those patients had long-term survival and some have even been cured," Bruner says. "That is miraculous. But only 10 percent of lung cancer patients have the EGFR mutation, and only 10 percent of those patients experience the miracle."

Precision medicines come at another price: the possibility of side effects or even death.

"Some drugs, unfortunately, kill patients, and many of the side effects are terrible," Bruner notes. "Taste changes mean meals with family and drinks with friends will never bring the same pleasure again. Ulcers in the mouth mean you can't eat or drink at all. Blisters on your hands and feet mean you can't walk or touch or hold your child or play the piano. These side effects have not gotten enough attention. We are paying a lot of attention to cures but not to living with these cures."

Emory is an international leader in developing ground-breaking cancer treatments. It is also a leader in symptom science and quality of life.

"Precision medicine is not just genetics or immunotherapy," Bruner says. "Real precision medicine also takes into account environmental and lifestyle factors and puts them all together. How do we make sure a patient gets a $10,000 drug at home and takes it at noon and bedtime with the other drugs they are allowed to take? That is symptom science, and we have great nurse scientists at Emory who are studying that."

Addressing disparities

Bruner has helped strengthen symptom science at the School of Nursing through her own work and the work of junior faculty whom she has mentored.

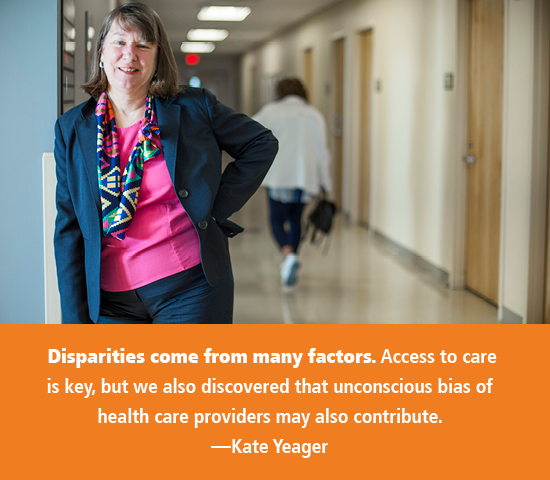

Among them is Kate Yeager 84N 12PhD FAAN, an assistant professor whose research focuses on health disparities related to symptom and pain management, adherence, and increasing minority enrollment in clinical trials, primarily African American cancer patients.

Yeager worked as a cancer nurse for a decade before earning her master's degree in oncology nursing at University of California–San Francisco, where she "caught the research bug." She returned to Emory in 2004 as a clinical research project manager. After years of supporting other experts' studies, she earned a PhD in nursing research. During her doctoral studies, "I discovered that your treatment options and cancer outcomes may vary based on your skin color," Yeager says.

Additionally, "African Americans are more likely to be diagnosed with cancer at a later stage, and their symptoms may be different or more severe," she has found. "These disparities come from many factors. Access to care is key, but we have also discovered that unconscious bias of health care providers may also contribute. Studies have shown that, compared with others, African Americans can go to the emergency room for the same injury, such as a fractured bone, and get different treatments. They may get less pain medication compared with white patients with the same diagnosis."

Citing the 2002 Institute of Medicine report Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Yeager notes that research demonstrates significant variation in the quality of medical care by race, even when insurance status, income, age, and severity of conditions are comparable. This research indicates that U.S. racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to receive even routine medical procedures and experience a lower quality of health services.

"This report has done a lot to describe this pattern of inequitable care, but we have more work to do to reduce these health disparities," says Yeager. She just finished gathering data for an NIH-funded project examining individual, social, and neighborhood factors in opiate pain medication adherence among African American cancer patients. While final study results are pending, the data clearly show that multiple factors play a role in medication adherence.

"We have the medications to help people with their symptoms," she says. "We need to have a more personalized approach on how they are prescribed, and we need to teach people how to better communicate with their health care providers."

Another aspect of Yeager's research seeks to extend care to underserved populations. As co-chair of the NRG Oncology Health Disparities Committee sponsored by NCI, Yeager works with colleagues around the country to better understand health disparities and identify barriers to enrollment of underserved populations in clinical trials.

At Winship Cancer Institute, she also completed a study to develop and test two recruitment videos for breast cancer clinical trials. One video targets African American women, and the other all other patients. Her pilot project aims to standardize education on breast cancer trials and learn how providers influence patients' decisions to participate in clinical trials.

"Only 3 percent of all cancer patients participate in clinical trials, and the minority percentage of that 3 percent is very small," Yeager says. "We have completed surveys across the NRG Oncology cooperative group to better understand what works and what does not."

Alleviating cancer fatigue

What about the microbiome?Deborah Bruner thinks we need to pay more attention to our bugs. Her current research is in the arena of the microbiome, or "the collection of all the micro-organisms living in association with the human body," as defined by the NIH Human Microbiome Project. She correlates the importance of microbiome research to the launch of the Human Genome Project in 1990. In a Winship Cancer Institute pilot study on cervical and endometrial cancer, Bruner is examining changes in patients' vaginal microbiome that were thought to be related to post-treatment symptoms. "We found that prior to treatment, women already had an abnormal vaginal microbiome. So that begs the question: Did cancer change the microbiome, or did the microbiome promote cancer? We hope to be on the forefront of answering some of those questions," she says. A tremendous amount of work also is emerging on the "gut-brain axis," the biochemical signaling that takes place between the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system. In another Winship pilot study, Bruner is looking at the gut-brain axis in chemotherapy and breast cancer based on the phenomenon of "chemo brain," a common term used by cancer survivors to describe thinking and memory problems that can occur after their treatment. "Chemo brain has been very hard to explain," Bruner says. "When you do neurocognitive batteries, you don't find abnormalities, yet it is a consistent symptomatic complaint. It may be that we haven't had the right pathways and metrics to discover the cause. It may be a change that occurs when you destroy the normal microbiome through chemotherapy, which may affect the brain."—MML |

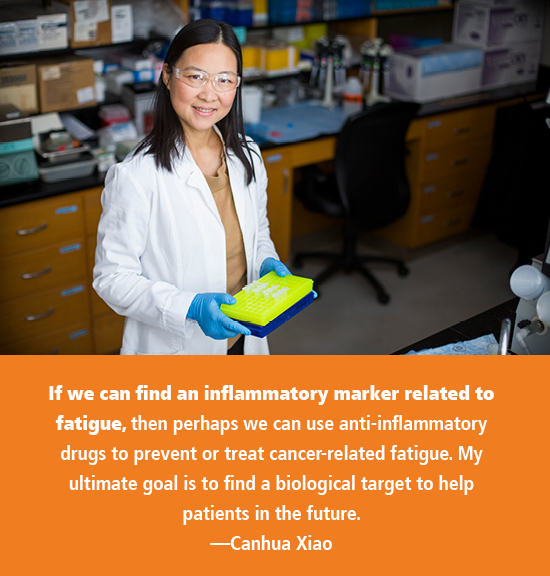

Canhua Xiao PhD RN, assistant professor, came to Emory as a postdoctoral fellow to work with Bruner, who was her PhD adviser at University of Pennsylvania. Bruner was instrumental in helping Xiao hone her research interests.

While a postdoc, Xiao earned a five-year NIH Pathway to Independence award to study the role of pro- and anti-inflammatory signaling in fatigue in head and neck cancer patients. This year, Xiao received a $1.5 million National Institute of Nursing Research grant to study the epigenetic mechanisms of inflammation and fatigue in the same patients.

"We are looking at people who are receiving radiotherapy, particularly a technique called IMRT (intensity modulation radiation therapy)," explains Xiao. "Compared with traditional radiotherapy, IMRT can target more of the radiation dose to the tumor while avoiding normal tissue. This technology can reduce radiation-related side effects. It is shown to reduce symptoms of dry mouth, but for some reason, people receiving this new type of radiotherapy experience more fatigue."

Although fatigue is the most common side effect of any cancer treatment, it is unclear why head and neck cancer patients experience high rates of severe fatigue. Patients with these cancers—which occur in the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, salivary glands, paranasal sinuses, and nasal cavity—experience other side effects at a higher rate than other cancer patients.

"If we can find an inflammatory marker related to fatigue, then perhaps we can use anti-inflammatory drugs to prevent or treat cancer-related fatigue," says Xiao. "My ultimate goal is to find a biological target to help patients in the future."

A life worth living

Walter Curran, executive director of Winship Cancer Institute, began working with Bruner in the 1980s when he was a junior faculty member at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia and Bruner was chief nurse in the radiation oncology department.

"Deb is a major leader of research who looks at outcomes rather than tumor response and survival," Curran says. "In quality-of-life factors like patient symptoms, she really is one of the national leaders in defining the metrics for factors that can't be measured by doctors and caregivers. They had to be measured by patients themselves for incorporating into research."

That point is not lost on Linda McCauley, dean of the School of Nursing. "As nurses," she says, "we really can see things we believe other health professionals don't ever get to see because of the level of trust patients give us."

While Bruner has been long away from clinical nursing, her research and that of other Emory nurse scientists is driven by a desire to minimize the physical, emotional, and financial effects of cancer treatment on patients and families.

"We need more research and more research funding dedicated to care and compassion," she says. "Care and compassion is mostly a nurse, standing at a bedside, trying to care for a human being and trying to give them not just a long life, but a life worth living."