Environment, the Microbiome, and Preterm Birth

By Pam Auchmutey

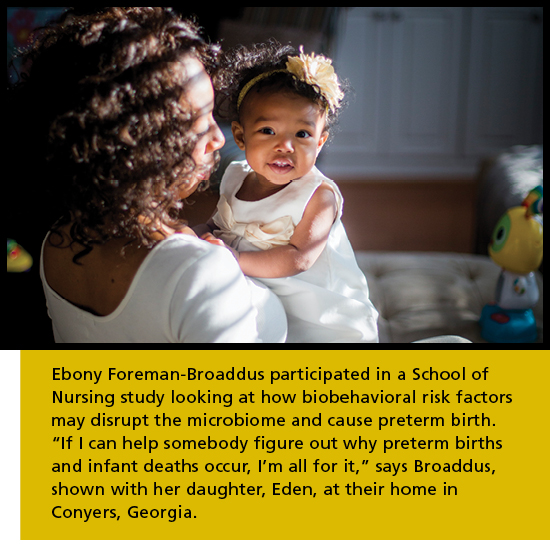

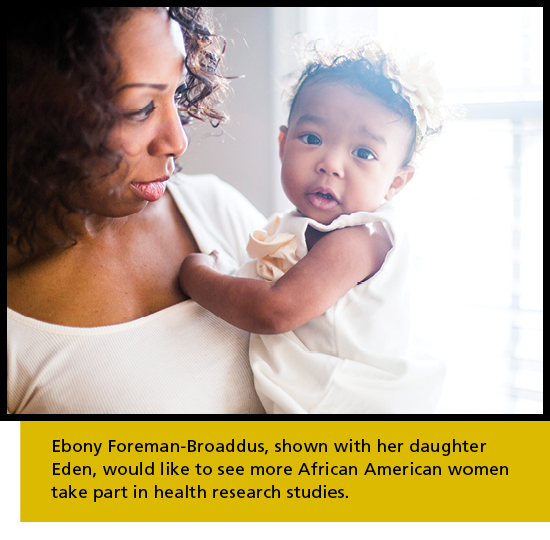

Ebony Foreman-Broaddus participated in a School of Nursing study looking at how biobehavioral risk factors may disrupt the microbiome and cause preterm birth.

Ebony Foreman-Broaddus participated in a School of Nursing study looking at how biobehavioral risk factors may disrupt the microbiome and cause preterm birth. A team of School of Nursing researchers assess Tiunca Cameron’s infant daughter, Tykeriah, at her home in Atlanta. The mother and daughter are participants in related studies examining how the microbiome affects their health.

A team of School of Nursing researchers assess Tiunca Cameron’s infant daughter, Tykeriah, at her home in Atlanta. The mother and daughter are participants in related studies examining how the microbiome affects their health. A team of School of Nursing researchers assess Tiunca Cameron’s infant daughter, Tykeriah, at her home in Atlanta. The mother and daughter are participants in related studies examining how the microbiome affects their health.

A team of School of Nursing researchers assess Tiunca Cameron’s infant daughter, Tykeriah, at her home in Atlanta. The mother and daughter are participants in related studies examining how the microbiome affects their health. A team of School of Nursing researchers assess Tiunca Cameron’s infant daughter, Tykeriah, at her home in Atlanta. The mother and daughter are participants in related studies examining how the microbiome affects their health.

A team of School of Nursing researchers assess Tiunca Cameron’s infant daughter, Tykeriah, at her home in Atlanta. The mother and daughter are participants in related studies examining how the microbiome affects their health. Nursing school faculty and students prepare kits used to collect biological samples from mothers and babies.

Nursing school faculty and students prepare kits used to collect biological samples from mothers and babies. Kits prepared by the Nursing school faculty and students. The kits are used to collect biological samples from mothers and babies.

Kits prepared by the Nursing school faculty and students. The kits are used to collect biological samples from mothers and babies. Linda McCauley (nursing, left) and Barry Ryan (public health, right) are dual principal investigators of C-CHEM2.

Linda McCauley (nursing, left) and Barry Ryan (public health, right) are dual principal investigators of C-CHEM2. Anne Dunlop (nursing, left) confers with Dana Boyd Barr (public health, right) in the leader lab at the Rollins School of Public Health.

Anne Dunlop (nursing, left) confers with Dana Boyd Barr (public health, right) in the leader lab at the Rollins School of Public Health. Postdoctoral fellow Irene Yang makes a home visit to collect samples and data from Precious Leeks for the maternal microbiome study, which currently involves about 300 pregnant African American women in the Atlanta area.

Postdoctoral fellow Irene Yang makes a home visit to collect samples and data from Precious Leeks for the maternal microbiome study, which currently involves about 300 pregnant African American women in the Atlanta area. Postdoctoral fellow Irene Yang makes a home visit to collect samples and data from Precious Leeks for the maternal microbiome study, which currently involves about 300 pregnant African American women in the Atlanta area.

Postdoctoral fellow Irene Yang makes a home visit to collect samples and data from Precious Leeks for the maternal microbiome study, which currently involves about 300 pregnant African American women in the Atlanta area. Postdoctoral fellow Irene Yang makes a home visit to collect samples and data from Precious Leeks for the maternal microbiome study, which currently involves about 300 pregnant African American women in the Atlanta area.

Postdoctoral fellow Irene Yang makes a home visit to collect samples and data from Precious Leeks for the maternal microbiome study, which currently involves about 300 pregnant African American women in the Atlanta area. Dean Jones (medicine) will map the metabolic pathways of mothers and their infants.

Dean Jones (medicine) will map the metabolic pathways of mothers and their infants. Priya D’Souza (public health) analyzes environmental samples.

Priya D’Souza (public health) analyzes environmental samples. Patricia Brennan (psychology, left) and Jeannie Rodriguez (nursing,right) will look at how environment affects infant neurodevelopment.

Patricia Brennan (psychology, left) and Jeannie Rodriguez (nursing,right) will look at how environment affects infant neurodevelopment. Community members gather for their first C-CHEM2 advisory board meeting.

Community members gather for their first C-CHEM2 advisory board meeting. Barry Ryan (left) and Linda McCauley (right) welcomed the community members gathered for their first C-CHEM2 advisory board meeting.

Barry Ryan (left) and Linda McCauley (right) welcomed the community members gathered for their first C-CHEM2 advisory board meeting. Maeve Howett welcomed the community members gathered for their first C-CHEM2 advisory board meeting.

Maeve Howett welcomed the community members gathered for their first C-CHEM2 advisory board meeting.

Ebony Foreman-Broaddus knows she is fortunate. She and her husband served with the Marines in Iraq before they married. They now enjoy a comfortable life in Conyers, Georgia, where they are raising two sons, ages 8 and 6, and a daughter, age 1. All are healthy and were born full term.

Broaddus is well aware that other African American women often experience adverse birth outcomes. Women in her racial group have a 1.5 times higher risk of preterm birth than Caucasian women, a statistic that makes preterm birth the leading cause of infant mortality in the African American population. While pregnant with her daughter, Broaddus enrolled in a School of Nursing study examining the underlying causes of preterm birth among some 500 pregnant African American women in metro Atlanta. The study, and research in general, are important to her.

“If I can help somebody figure out why preterm births and infant deaths occur, I’m all for it,” says Broaddus. “My sister passed away from SIDS [sudden infant death syndrome] when she was a few months old, so I want to do anything I can to help. I know a lot of African American women who have this notion that they don’t need to participate in research. When things happen to them they will say, ‘why wasn’t I told about this or why didn’t I know about this?’ We all need to expand our mindset and open our eyes to learn why certain things happen to us and our children.”

Specifically, Broaddus is helping researchers understand how biobehavioral determinants—the biological, social, behavioral, and environmental factors of health—influence the microbiome of African American women during pregnancy and whether disruption of the microbiome—the trillions of microbes that populate the body—may cause preterm birth.

To date, nearly 300 expectant mothers ages 18 to 35 have enrolled in the longitudinal study, led by nursing researchers Elizabeth Corwin PhD RN FAAN and Anne Dunlop MD MPH and funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research. Participants agree to provide biological samples—via oral, vaginal, and rectal swabs and blood draws—during two prenatal clinic visits (at eight to 14 weeks and 24 to 30 weeks of pregnancy) at Grady Memorial Hospital or Emory University Hospital Midtown. Data also are collected from their medical records after their babies are born.

Researchers are analyzing the women’s samples in Emory laboratories to characterize the structure and dynamics of the vaginal, oral, and gut microbiome in order to determine which microbiome patterns may be linked to preterm birth. And they are identifying how biobehavioral determinants affect each microbiome during pregnancy.

Launched in 2014, the maternal microbiome project has yielded preliminary data for more than 250 women, with microbiome analysis completed for 50 women. To date, there has been a study retention rate of nearly 90 percent during pregnancy and a preterm birth rate of 15 percent. At least half of these women have experienced childhood trauma, such as family disruption, emotional or sexual abuse, and neglect. Income levels range from low to high.

|

|

“We’re learning that this is a very high-risk group of women,” says Corwin of the cohort.

The maternal microbiome study led by Corwin and Dunlop will yield results in other ways. It forms one pillar of a new children’s environmental health center involving four Emory University units—the School of Nursing, Rollins School of Public Health, the School of Medicine and Emory College of Arts and Sciences.

Formed last fall, the Center for Children’s Health, the Environment, the Microbiome, and Metabolomics (C-CHEM2) is gearing up to study factors affecting the environment of fetus and child and their impact on birth outcomes and the microbiome and neurodevelopment of infants.

One of 15 children’s environmental health centers in the nation and the only one in the Southeast, C-CHEM2 is the first such center to be based in a nursing school and to focus on the microbiome. Funding support totaling $5 million comes from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The grant is the largest ever awarded to Emory's nursing school by the National Institutes of Health.

When the federal agency issued a call for proposals to study children’s environmental health with an emphasis on disparities, Linda McCauley, dean of the School of Nursing, and Barry Ryan PhD MS, professor of environmental health at Rollins, began talking. Both are experts in conducting community-based research on exposures to environmental toxicants and serve as dual principal investigators for C-CHEM2.

“Dr. Ryan pulled a lot of people together to talk about submitting a proposal, and it soon became clear that we were the program with a pillar study already in place,” Corwin explains. “We had a cohort of pregnant African American women who had delivered or were about to deliver and a pending follow-up study of their infants that fit the children’s health center concept well. From that point on, everything came together and the C-CHEM2 team was formed.”

“Health disparities start prenatally or even preconceptually,” adds Dunlop, who is using the same cohort to study the epigenetics of preterm birth with School of Medicine colleague Alicia Smith PhD. “It’s critical to initiate the investigation of the factors shaping child health disparities in the womb as early as possible during pregnancy.”

An understudied population

As the researchers point out, prior studies have shown that urban minorities are at elevated risk for environmental exposures and adverse birth, health, and developmental outcomes. But none has characterized environmental exposures among residents in the urban Southeast, regarded by researchers as distinct in terms of housing, climate, traffic, diet, culture, and racial/ethnic makeup. Atlanta’s African Americans embody those characteristics.

C-CHEM2 will zero in on this population by leveraging data generated by the maternal micro-biome study in the School of Nursing and the laboratory resources of the HERCULES Center (Health and Exposome Research Center: Understanding Lifetime Exposures) at Rollins. Led by Parkinson’s disease expert Gary Miller, HERCULES is the first research center in the nation to measure the exposome—the cumulative impact of lifelong environmental exposures on health. Women in the maternal microbiome study, along with their infants in a related follow-up study, will help characterize these lifetime exposures and their effects.

The infant microbiome study, funded by the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities and co-led by Corwin and Emory College psychology professor Patricia Brennan PhD, is examining how chronic maternal stress and disadvantage may affect the microbiome-gut-brain axis of infants.

The investigators are looking for possible links between maternal stress during pregnancy and the composition of the maternal and infant gut microbiomes and whether their composition affects the cognitive and social-emotional development of babies.

Their study relies on samples collected from women in the maternal microbiome study and infant samples collected by researchers during five home visits beginning one week after birth and ending at 18 months.

“Many factors that influence the microbiome are modifiable,” says Corwin. “These may include changing your diet or avoiding use of a certain type of perfume or household cleaner. Once we know what behaviors are beneficial, we can develop interventions to minimize risk. The knowledge gained from these studies holds tremendous potential for promoting the health of the next generation of African American families.”

Exposures in the home

C-CHEM2 shares that potential as researchers conduct three related environmental exposure projects using biological samples from the maternal and infant microbiome studies as their foundation.

CHERUB (Characterizing Exposures and Outcomes in an Urban Birth Cohort), the first project, will characterize the environmental exposure of mothers and their infants, based on serum and urine samples collected from women during their prenatal visits. Researchers also will visit their homes to collect infant blood and urine samples and dust and air samples. All of these samples will be analyzed in the leader lab under the direction of Dana Boyd Barr PhD, the analytical core director for HERCULES, and Dunlop.

Project leaders and staff will examine samples for the presence of air pollutants and chemicals that women and children may be exposed to in the home. Their list includes phthalates (found in perfumes, fingernail polish, house paint, and time-release medications), bisphenol A or BPA (the plasticizer that lines food cans), perfluorinated chemicals (in pizza and microwave popcorn packaging), brominated flame retardants or BFRs (used in electronics, plastics, and textiles), parabens (antimicrobials), and pesticides.

All of the samples collected will be analyzed using mass spectrometry, which will measure the concentration of each chemical to which each woman is exposed.

Granted it’s widely known that BFRs disrupt hormone production in the thyroid and that pesticide exposure during pregnancy has been linked to neurodevelopment deficits in infants. So why study them again?

“The impetus for this project is that we don’t know much about these types of exposures in the Southeast,” says Barr. “And there’s no other center looking at them in the Southeast. It’s an ideal opportunity to understand what African American women in this cohort are exposed to and also determine the most relevant exposures.”

Exposures and infant development

Jeannie Rodriguez PhD RN C-PNP/PC has been a pediatric nurse for 20 years. As a junior faculty member in the School of Nursing, she is intent on expanding her research skills to study health problems in vulnerable children. C-CHEM2 affords her that opportunity by working with mentor Patricia Brennan on the center’s second project, called MEND (Microbiome, Environment, and Neurodevelopmental Delay), to determine how prenatal and postnatal toxicant exposures influence the infant gut microbiome and neurodevelopment and behavior during the first 18 months of life.

Researchers are just beginning to follow the cohort of African American mothers as they begin to deliver their infants. They will evaluate infants in the home by assessing their cognitive and social-emotional development and collecting blood and stool samples to evaluate environmental exposures and characterize gut microbiome composition.

This project, researchers say, will deepen their understanding of the complex relationships between infant microbiota and environment. It may also help explain why some individuals are more susceptible to environmental exposures than others and thus revolutionize current approaches to toxicity testing.

As a psychologist, Brennan is interested in the specific factors that contribute to prenatal risk among African American women. Maternal stress is high on the list.

“The primary aim of our project is looking at the impact of stress and toxicant exposures on infant neurodevelopment,” Brennan says. “The microbiome may be an important risk mechanism because it influences development of the brain, the immune system, and other functions. They’re all tied together in the gut-brain axis.”

In time, MEND’s results may influence nursing practice. “A big role in nursing is assessment and screening. In pediatrics, we focus a lot on health promotion and disease prevention,” says Rodriguez. “Understanding how prenatal and postnatal toxicant exposures influence health could eventually guide us in what to screen for and modify in order to promote more optimal health outcomes in childhood and beyond.”

Metabolic pathways and preterm birth

At the heart of C-CHEM2 is the desire to understand why so many African American women experience preterm birth. The field of metabolomics is key to understanding why this happens. It allows scientists to look at the chemical reactions that take place in the body. By measuring metabolic pathways in tissues and cells, scientists can pinpoint disturbances—or biomarkers—that indicate health or disease risks

A third center project, known as MATRIX (Metabolomic, Microbiome, and Toxicant-Associated Interactions), will use high-resolution mass spectrometry to map the metabolic pathways of mothers and their infants. These data will be used to determine which biomarkers (disrupted pathways) are associated with preterm births and cognitive disorders in young children.

Dean Jones PhD, director of the Clinical Biomarkers Laboratory in the School of Medicine, and Corwin, a physiologist and family nurse practitioner, are partners on the project, which ultimately could lead to new screening and intervention methods to prevent preterm births and adverse brain outcomes for infants specific to the African American population.

Jones pioneered development of the ultra high-resolution metabolomics platform to provide detailed data on environmental as well as dietary, infectious, behavioral, and stress-related exposures. High-resolution metabolomics provides the foundation for establishing a cumulative record of these exposures. The technology used in the Clinical Biomarkers Laboratory allows scientists to analyze the 20,000 chemicals present in a drop of blood with relative ease. Essentially, MATRIX will provide a metabolic profile for every study participant in C-CHEM2.

“In our analysis, we will look at chemicals that are present and identify whether they are derived from food, the microbiome, or the environment,” Jones says. “We’re not targeting any of them. We’re seeing what’s there.”

Based on that data, MATRIX will look for associations between environmental and microbiome factors with preterm births and infant neurodevelopmental outcomes.

“This project is addressing the high frequency of preterm births among African Americans in urban Atlanta,” says Jones. “This study will help determine if it’s caused by environmental factors that we can identify. If that’s the case, then we have an opportunity to do something about it—to change policies to implement practices to try to correct the problem.”

Not everyone exposed to a particular risk factor will experience adverse health effects or disease, notes Corwin. “Metabolomics is a way to more precisely identify those who are adversely affected by an exposure without waiting for an outcome or disease to occur.”

Community-driven science

Once babies learn to crawl, they scamper across carpets that contain protective chemicals or floor that bear traces of dust no matter how clean. They check things out by putting fingers and items of interest in their mouths. When held in their mothers' arms, they may drink from a plastic bottle and wear a sleeper treated with a chemical flame retardant.

Maeve Howett PhD APRN CPNP-PC IBCLC CNE knows these hazards all too well. She teaches nursing students about environmental health and serves with the Southeast Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit, which educates families, communities, and health care providers about how to protect children from environmental exposures. Howett also leads the C-CHEM2 Community Outreach and Translation Core (COTC) in collaboration with Melanie Pearson PhD, director of research projects in the Department of Environmental Health at Rollins.

In January, Howett and Pearson convened the first meeting of the COTC Stakeholder Advisory Board. Its members include representatives from Atlanta-area nonprofit groups that serve African American women, children, teens, parents and grandparents; local public schools; and Morehouse School of Medicine.

“Our study population of interest is urban African American women of child-bearing age, so it’s important that we reach out to that community,” Howett says of the COTC. “The west side of Atlanta has an exceptionally high rate of preterm birth that is unacceptable to us. We want our advisory board to tell us what our scientists should study and the best ways to share what we learn.”

The COTC, says Barry Ryan, is a two-way street. “We listen to community members. They listen to us. We give them feedback. They give us feedback. And in both cases, we learn something.”

The next frontier

In the long run, C-CHEM2 has the potential to change health care. It’s already changing nursing education, given the number of graduate students who are involved in C-CHEM2 projects.

Sheila Jordan 10MPH 11N is a PhD student who is helping collect samples from pregnant women during their prenatal visits at Emory Midtown. She plans to study a subset of these women who have hypertension disorders for her dissertation. Thanks to the maternal microbiome study, she has an opportunity to connect with a research population that typically is hard to reach.

“It’s very hard to recruit pregnant women,” says Jordan. “Recruiting African American women who are pregnant can be an even greater challenge. I found a diamond in the rough. I couldn’t have asked for anything better.”

“What this study brings to the table that others have lacked is a connection between what happens during a pregnancy and subsequent newborn development,” she adds. “We’re able to pull a lot of psychosocial and biological variables from the pregnancy and see how they affect infant outcomes. That’s a research gap that’s been missing in the maternal-child literature.”

C-CHEM2 projects also underscore the need for nurse clinicians to stay abreast of new frontiers in science. “Being the trusted cornerstone of health care, nurses have to be on top of this,” Jordan says. “We’re the ones patients turn to for information.”

That’s exactly what School of Nursing faculty members like to hear, especially Dean Linda McCauley.

“The reason I wanted this center so much is to make environmental health the fabric of the work of all the nurses who graduate from Emory,” she says. “I want it to become part of how they interact with all of their patients. I want them to have an in-depth understanding of how important it is to decrease our exposures to air pollution and other exposures that we know can harm health. My hope is that we can sensitize nurses and physicians to do more of this work. Quite simply, they are the ones who interface with the community.”

Video

|