Taking Care of Business

By Laura Raines

Laura Prado is the first graduate of the DNP program. She studied in the leadership track in order to play a more active role at Atlanta Brain and Spine Care, where she sees patients before, during, and after surgery.

This past summer, Laura Prado 95N 99MN reached a milestone in her career and for the School of Nursing as the first Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) graduate.

The School of Nursing launched its DNP program in 2014 for compelling reasons. Given the vast changes in care delivery and reimbursements, nurses must partner fully with physicians and other clinicians to redesign health care practice and systems. Also, the Institute of Medicine’s 2010 report on The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health called for higher levels of education to prepare nurses as leaders in health care, research, and education. Now Prado is among those leading the way.

“It’s been exciting to be in on the start of something new and see it evolve,” she says. In 2015, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) counted 264 DNP programs in the United States, including Emory’s.

“My BSN and MSN degrees are from here, and I knew the program would be quality,” she says. “I was already confident in my clinical skills, but I wanted to take my practice to the next level. I knew a DNP degree would give me more options.”

A nurse practitioner (NP) with Atlanta Brain and Spine Care, Prado sees patients before, during, and after surgery. Not many NPs work in a surgical setting, she notes, but “going into the operating room allows me to give greater continuity of care to my patients.”

The leadership track has given her the business skills to take a more active role in her organization.“Health care is a constantly evolving environment. You have to understand more than clinical skills,” she says. “I’d like to publish, design more quality-improvement projects, and encourage more NPs to work in this specialty, maybe teach.”

For her DNP project, Prado measured pre- and post-op anxiety in her patients by survey. “Fear of the unknown” and “knowledge deficits” caused anxiety. Time spent with patients answering questions and supplying information relieved it. Coursework helped her define a clinical issue and collect and analyze data to find a solution.

“I was thrilled to get a statistically significant finding,” she says. “It showed that patients really liked knowing that the NP was in the OR and understood their entire surgical experience. My time and care adds value to the practice and makes a difference.”

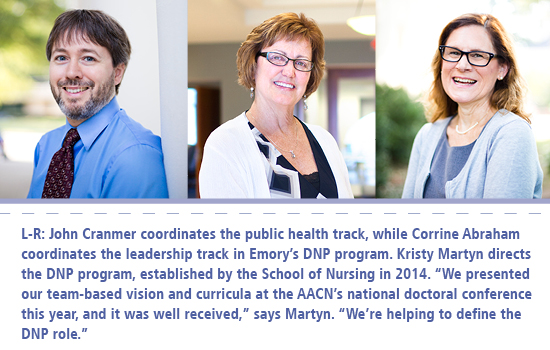

The fact that students design and drive their own DNP projects in partnership with an academic team and their clinical site—a three-way partnership—is at the heart of Emory’s DNP program, says its director, Kristy Martyn PhD RN CPNP-PC FAAN. “The AACN published a paper on DNP essentials in 2006, but there weren’t a lot of specifics about what DNP projects should be,” she says. “An AACN task force gave clearer guidance in 2015, and we were already doing what they recommended.” Accordingly, DNP projects are grounded in a particular practice with a goal of transforming health care and improving outcomes.

By waiting to develop its DNP program, Emory was able to learn from other schools. “Our faculty created a clear vision and adopted a model of continuous improvement and collaboration. That makes our program what it needs to be,” says Martyn.

An advisory board of diverse health care leaders weighs in on what skills and knowledge are needed to lead in today’s hospital systems, clinics, public health settings, and health care organizations. Students may pursue one of two tracks: health systems leadership and population health.

“Our vision is that Emory DNP graduates transform health,” Martyn continues. “Nurses previously learned leadership on the job, but with advances in science and technology, health care is more complicated. Nurses need to be at the table when decisions are made, when innovative solutions are implemented. DNPs are prepared for that kind of leadership.”

A hybrid program that works

|

Sharon Vanairsdale, a first-year DNP student, is program director of the Serious Communicable Diseases Unit at Emory University Hospital. She just received the 2016 National Magnet Status of the Year Award for Exemplary Professional Practice. |

Population health isn’t available in many DNP programs, but it made sense in Atlanta says the track’s coordinator, John Cranmer DNP MPH MSN ANP-BC. “Our faculty expertise and our partnerships with the Lillian Carter Center for Global Health & Social Responsibility, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Rollins School of Public Health put Emory in the position to offer it.”

Designed to accommodate working nurses with diverse experiences, Emory’s hybrid DNP program is taught mostly online, but students come to campus three Saturdays a semester for workshops and guest speakers.

“We knew we wanted to personalize their education. There was no need to duplicate what they already knew. Our goal is to build on it,” says Corrine Abraham 85MN DNP RN, coordinator of the health systems leadership track.

In one course, students use a leadership skills assessment instrument to learn their strengths and weaknesses and craft a proposal for meeting the course requirement.

“One student already had started a business but had never taken a course in finance,” says Abraham. “To fill that gap, we proposed that he serve as a teaching assistant for the finance course, which would give him additional subject expertise and teaching experience.”

|

Erin Biscone is a nurse-midwife at Baylor College of Medicine. She enrolled in Emory’s DNP program to gain business and leadership skills to push for reopening the nurse-midwifery school at Baylor. |

Abraham refined her criteria for a DNP education while serving as a nurse fellow in the VA Quality Scholars Program (2012–2014), where she focused on enhancing the quality and safety of health care for veterans through inter-professional strategies. “What’s needed in DNP education is for the learning to be salient and integrated into the students’ practice. You can’t have a cookie-cutter program,” she says.

It takes a flexible, highly engaged, and collaborative faculty to make student-centered learning work. Constant communication and twice-annual retreats continuously help improve the curricula and clinical partnerships.

“We’re committed to the product, the outcomes, and we want the highest quality,” Abraham adds. In preparation for this fall, faculty adapted the program for BSN-prepared students with less work experience and training in order to build leaders from the get-go.

And while many other DNP programs are taught by PhDs, five out of six DNP faculty members at Emory hold a DNP. “We’re a small program, but the number of DNP faculty with different specialties makes us unique,” Abraham notes. “Our focus isn’t on research but on practice improvement, translating evidence to practice, and clinical leadership.”

Reviving nurse-midwifery education in Texas

DNP student Erin Sing Biscone CNM RN, who will graduate this fall, wanted a project to broaden nurse-midwifery in Texas. A nurse-midwife delivered her second child, but soon after she saw nurse-midwives lose hospital privileges and nurse-midwifery programs close in her state. “Something had to be done,” says Biscone. “I became a nurse and a nurse-midwife (in 2008) in order to advocate for the profession.”

Today she practices with Baylor College of Medicine in Houston and is active in the American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM). Her ultimate goal: to reopen the nurse-midwifery school at Baylor, which closed in 2004–2005. She turned to Emory’s DNP program to expand her business and leadership skills.

For her DNP project, Biscone studied the discrepancy in the number of midwifery deliveries, compared with the number actually listed on birth certificates. “ACNM suspected that midwife deliveries were being under-reported, with just the physician’s name listed on the birth certificate, and that spoke to me,” says Biscone. She surveyed licensed nurse-midwives in Texas to see how often they’d been listed on birth certificates, aiming for greater reporting accuracy.

“Health care is a business, and nurses need business and leadership skills in order to advance change,” says Biscone. “That’s what Emory delivers. I appreciate the rigor and the responsiveness of faculty.”

Cranmer has embraced his role as a DNP coach and mentor to students like Biscone. “We recruit students who function at a high level, and we partner with them to create practice innovation and transformation,” he says.

For his part, Cranmer teaches students how to analyze data and how to ask the “so what?” questions such as, “What does it mean for the individual practice setting?”

“You’re looking at data from the big picture to create strategies for individual populations and patients,” he explains. “With these skills, the next hospital systems consultant or government policymaker could be a DNP. This is still an evolving credential, and our graduates will need to know how to write their own job descriptions. They’re developing the skills to do that.”

Emory To Offer CRNA Program

In 2017, the School of Nursing plans to enroll the inaugural class in a new DNP Nurse Anesthesia Program. Only the second such program in Georgia, it is sorely needed, says Elaine Fisher PhD RN CNE, director of accreditation and curriculum for the school. Georgia has 25 percent fewer nurse anesthetists than the national average. Also, about 50 percent of American CRNAs (certified registered nurse anesthetists) are expected to retire by 2022, and an aging population creates an even greater demand for their services.

|

Elaine Fisher |

The Council on Accreditation of Nurse Anesthesia Educational Programs (COA) requires that all CRNAs be doctorally prepared by 2025, making a nurse anesthesia track within Emory’s DNP program a perfect fit.

“Anesthesia is a very complex field, and students need to be educated to the highest level,” says Fisher. “They will go through a rigorous 36-month, full-time program designed to equip them with evidence-based, best-practices knowledge and the leadership skills needed to build teams in today’s health care environment.”

In the United States, CRNAs provide more than half of the anesthetics delivered each year, enabling, high-quality and cost-effective care. At Emory, the School of Nursing is building an operating room facility to teach competencies and began reviewing applicants for its CRNA program this fall. Kelly Wiltse Nicely PhD CRNA, a faculty member at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, will soon join Emory as CRNA program director. The program is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges. Final approval is pending from the COA.—Laura Raines