Supply & Demand

By Laura Raines, Photography by Stephen Nowland

Lower Oconee Community Hospital closed a few years ago in Glenwood, Georgia—one of many rural towns affected by a fractured health care system, including a shortage of nurses.

More than 4 million strong, nurses are the largest profession in the U.S. health care sector. Yet, as experts have predicted for some time, the nation faces a critical shortage of nurses stemming from a wave of nurses reaching retirement age and an aging population that relies heavily on nursing care.

Emory’s School of Nursing took on the problem last summer by launching the Georgia Nursing Workforce Initiative. Housed within the School’s Center for Data Science, the project is funded with a $200,000 grant from the Robert W. Woodruff Foundation.

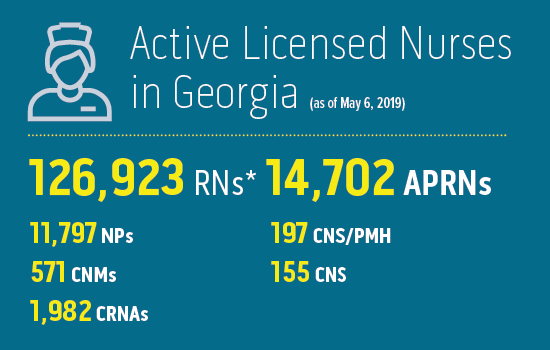

“Our first goal is to determine what the supply of nurses looks like in Georgia,” explains Associate Professor Jeannie Cimiotti PhD FAAN, a health services researcher and expert in nurse workforce issues and quality of patient care. “We want to know nurses’ level of educational preparation, whether they are registered nurses (RNs) or advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), where they live, and where they practice.”

Jeannie Cimiotti and Yin Li are analyzing workforce data to address Georgia's nursing shortage, especially in rural areas.

Jeannie Cimiotti and Yin Li are analyzing workforce data to address Georgia's nursing shortage, especially in rural areas.

The initiative stemmed in part from Dean Linda McCauley’s role in the Georgia Nursing Leadership Coalition (GNLC) and its 2015 report on the Registered Nursing Workforce in Georgia. That report analyzed data from the Georgia Board of Nursing (GBON) workforce surveys, part of nurses' online relicensure process since 2011. While survey participation is now 86.7 percent, the data are not exhaustive.

“We are in the process of locating and gathering data from other sources in order to put together a more complete picture of nursing in Georgia,” says Assistant Research Professor Yin Li PhD, who manages and analyzes large data sets.

She and Cimiotti are scrutinizing data from the American Community Survey of the U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics to augment the information obtained from the GBON survey.

According to the 2017 Health Resources and Services Administration report on Supply and Demand Projections of the Nursing Workforce: 2014–2030, national nursing demand will increase from 2,806,100 RNs in 2014 to 3,601,800 RNs in 2030. Many states are projected to have an undersupply of nurses, including Georgia, where the shortage will reach 2,200 nurses by 2030.

“We know that Georgia is going to have a greater need in some geographic areas and clinical specialties than in others,” says Cimiotti. “Many new nurses are attracted to the fast pace and high acuity of university hospitals and less inclined to work at small community hospitals and in long-term care.”

According to the GNLC report, fewer Georgia RNs work in gerontology and assisted living, nursing homes, and extended care facilities than the national average. Cimiotti and Li suspect that the rural/urban question will be important for the state. If their findings support greater shortages in rural areas, the data will help state health care leaders look for solutions. For instance: “They might adjust salaries to make working in rural areas more attractive,” notes Cimiotti.

The first product of Cimiotti and Li’s work is a 10-year longitudinal analysis of nursing in Georgia. Slated for publication this spring, the report will describe the demographic and employment characteristics of nurses, including where they work and at what salaries.

“After we have a descriptive report, we can begin to determine the specific demands and needs in the state,” says Cimiotti.

While various organizations have focused on the nursing shortage in general, few have looked at specifics, such as the need for more nurse practitioners in rural areas, the untapped resource of clinical nurse specialists, and the shortage of nursing faculty. In time, the researchers’ work may lead to establishing a major nursing workforce data center.

McCauley sees the data being used to address key health issues in Georgia, such as maternal mortality, infections, blood pressure control, healthy behaviors, rehospitalizations, and workforce needs in the face of major health crises such as flu or other pandemics. Understanding the nursing workforce, she says, is also crucial to helping transform models of care, which is one of the strategic goals of Emory’s Woodruff Health Sciences Center.

Source: Georgia Board of Nursing * Single State Licensure

Source: Georgia Board of Nursing * Single State Licensure