A Different Set of Tools

By Laura Raines, Photography by Stephen Nowland

Kylie Smith stands in the hallway of the building that housed the Georgia Mental Health Institute near Emory.

Nurses have always been advocates for better health and ‘bringers of good” to patients and populations. “It’s part of their mandate to care,” says Kylie M. Smith PhD, Andrew W. Mellon Faculty Fellow for Nursing and Humanities at the School of Nursing.

That’s why nursing students should engage with the humanities. “The nursing curriculum is necessarily technical, but studying the liberal arts, looking at ethics and social responsibility, gives nurses a different set of tools and language to deal with today’s complex health issues and diverse patient populations,” adds Smith, who teaches Nursing for Social Change, an elective open to all students, and co-teaches Evolution of Nursing Science, a requirement for doctoral students.

Nurses have a long tradition of advocating for social justice, but what that means has changed through history. Following the Nightingale role, nurses in the late 1800s were concerned with improving sanitary conditions in hospitals.

As the profession evolved to embrace community and public health, nurses provided care to people who otherwise would not receive it—disenfranchised, marginalized, and vulnerable populations, including immigrants. The Frontier Nursing Service, where nurses traveled on horseback into rural Kentucky, and nurses who practiced on Indian reservations exemplify nurses as sole providers. Nurses also were active in the suffragette movement. “They saw the vote as empowering them to better influence decisions made about practice, working conditions, and mother/baby care,” says Smith.

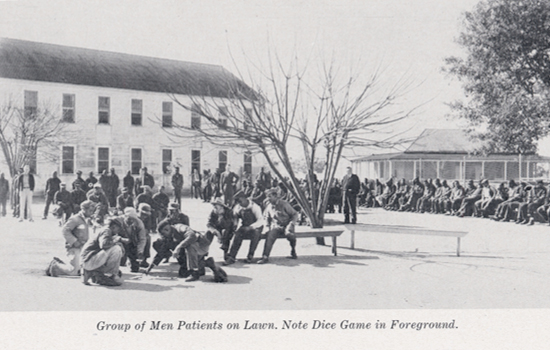

Bygone era: patients on the lawn of Searcy Hospital in Mobile, Alabama (Photo courtesy of University of Alabama-Birmingham)

Bygone era: patients on the lawn of Searcy Hospital in Mobile, Alabama (Photo courtesy of University of Alabama-Birmingham)During the 1950s and 1960s, the civil rights movement opened nurses’ eyes to the concept of patient rights as well as disparities in nursing education and practice. ‘Separate, but equal’ was anything but.

“When African American women tried to move into professional nursing, doors were shut for quite some time,” says Smith. But it was nurses who advocated for letting African American nurses into the Army Nurse Corp during World War II. At Emory, School of Nursing Dean Ada Fort fought to admit the first two African American nursing students in 1962. Threatened with losing its tax-exempt status, Emory went to court to argue that it had the right to establish its own admission policies. The Board of Trustees advised Fort to wait until the tax matter and the tensions of integration had settled some, but she persisted until both students were admitted.

Smith’s research into psychiatric/mental health nursing has taught her much about the importance of nurses’ taking a stand for social justice. Her book, Talking Therapy: Knowledge and Power in American Psychiatric Nursing, will be published by Rutgers University Press this year. Her research into Jim Crow in the Asylum: Psychiatry and Civil Rights in the American South will be published by the University of North Carolina Press in 2021.

The latter book “is not just about state hospitals and the deplorable and disparate conditions there, but also the people involved in that process,” Smith says. Her research will support a website with historic photos, court cases, records and interviews with civil rights lawyers and practitioners to better inform the public about mental health history and current needs.

“I talk to my students about the nurses who worked in those institutions,” she adds. “Some did nothing and were part of the problem. Others were whistle-blowers. It’s important to look at who had access to care and who got diagnosed with what, how there was a correlation between state hospital closings and a rise in prison numbers, and how laws were gradually changed. You can no longer lock anyone up without giving treatment. History reminds us that nurses can be part of the problem or the solution.”

Kylie Smith stands outside the Georgia Mental Health Institute building, which served as a psychiatric hospital from 1965 to 1997.

Kylie Smith stands outside the Georgia Mental Health Institute building, which served as a psychiatric hospital from 1965 to 1997.

While health conditions have improved for blacks and other populations, disparities still exist and access to care is a major issue for many. Nurses, for instance, are addressing the rights of LGBTQ patients and pushing back against biological racism. The humanities, Smith maintains, better equip nurses to be patient advocates and agents of system change. As caregivers, nurses have the ability to form relationships with their patients.

“In addition to being practitioners, nurses must be ethical problem-solvers,” says Smith. “It’s important for them to understand the multiple factors that contribute to their patients’ lives in order to care for the whole patient.”